Friday 29 April 2022

Brunei Darussalam: Report on External Sector Statistics Mission (Remote) (July 26-29, 2020)

Published April 29, 2022 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Thursday 28 April 2022

Malaysia: 2022 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Malaysia

Published April 28, 2022 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Wednesday 27 April 2022

Central African Republic: First Review Under the Staff-Monitored Program

Published April 27, 2022 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

ACLU: ICE Program Foments Abuse, Hatred, and Fear — and Makes Us All Less Safe

In 2017, Gerardo Martinez-Morales was driving to the doctor’s office when he was pulled over by sheriff’s deputies in Galveston County, Tex.. One week later, the father of four and grandfather of three who lived in the U.S. for more than two decades was deported to Mexico. The reason given for the traffic stop that caused him to be torn from his family of U.S. citizens? A broken taillight.

Under Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) 287(g) program, such travesties are all too common. The 287(g) program — named after a section of the 1996 Immigration and Nationality Act — sounds wonky, but is relatively simple and terribly life-altering in practice: It allows local law enforcement agencies, primarily sheriffs, to carry out certain duties normally reserved for federal ICE agents, such as investigating a person’s immigration status and holding people for transfer to ICE detention. The result is that even the most minor of interactions with local law enforcement can lead to detention, deportation, and separation from their families.

In a new research report, the ACLU found that dozens of sheriff partners in the 287(g) program have records of racism, abuse, and violence. Our analysis reveals that the majority of local partners have documented incidents of civil rights violations and other abuses. Our report makes clear that xenophobia is at the very heart of the program, which expanded five-fold under the anti-immigrant efforts of the Trump administration.

President Biden has continued to partner with sheriffs who entered into agreements with the Trump administration, despite promising to end them, and even though these partnerships undermine his administration’s stated priorities for criminal justice reform and immigrants’ rights.

https://infogram.com/1p6kvpjq2jerjza5gdx6qr5xq2c3rj5wjjv?live

While 287(g) is intended to be narrow in scope and proponents portray it as oriented towards deporting “criminals,” in practice, many sheriffs and their deputies wield their federally-delegated authorities quite widely. For years, local immigrant rights activists have documented racial profiling endemic to the program: sheriff’s deputies who look for any excuse to initially detain somebody they suspect of having a questionable immigration status — to funnel them into deportation.

Would Gerardo Martinez-Morales have been arrested for a “broken taillight” if he weren’t brown-skinned in an overwhelmingly white county policed by a sheriff who had pursued a 287(g) agreement and spoken publicly about the need to punish undocumented immigrants? Would the sheriff have pursued a 287(g) agreement in the first place if he weren’t on a mission to target immigrants?

After all, joining the program is voluntary under federal law and comes at local taxpayer expense with no measurable benefits. Studies suggest 287(g) undermines both public safety and public health as trust in local agencies plummets and fear rises. To better understand why a sheriff would still pursue a 287(g) agreement, it helps to look at the history of the program.

Nearly two-thirds of 287(g) partners have records of racial profiling and other civil rights abuses.

When Obama’s presidency ended, there were 34 remaining 287(g) agreements nationwide following several racial profiling investigations by the Department of Justice, including one that led to the termination of the 287(g) agreement in Alamance County, North Carolina. The Alamance County sheriff demanded deputies “bring me some Mexicans.” This led to incidents like that of a Latinx man who was arrested and later deported for “providing the wrong address for the crime scene” after he suffered a gunshot wound, or a Latinx women whose three young children were left alone for eight hours on the side of the highway at night after she was arrested and then deported for driving without a license.

Under the Trump administration, the program grew nearly five-fold in a few short years, reaching an all-time high of 152 participating agencies. Among the new agreements was one with the same sheriff in Alamance County.

This is no coincidence. Our investigation shows that the Trump administration actively recruited sheriffs to join the 287(g) program as part of the administration’s larger anti-immigrant agenda, and at the expense of civil rights.

As the ACLU report makes clear, xenophobia and rights abuses run rampant in the program. We find that 59 percent of 287(g) sheriffs have records of anti-immigrant rhetoric, and over half have expressly advocated inhumane federal immigration policies, in some cases while vowing to disobey any federal directives they disagree with. Nearly two-thirds of 287(g) partners have records of racial profiling and other civil rights abuses, while more than three-quarters operate detention facilities with documented patterns of abuse and inhumane conditions.

https://infogram.com/1pl63752m5zp9zfqmj1nwwmqz0f3k7721v?live

With a record this abysmal, there is no salvaging 287(g). As a candidate, President Biden pledged to “aggressively limit” 287(g), including by terminating all agreements entered under the Trump administration. But over a year into his administration, he has only ended one agreement.

Will President Biden make good on this promise to disentangle federal immigration enforcement from the everyday work of local law enforcement officers? Or will he continue to work with the very officials who perpetrate abuses, target immigrant communities, and undermine civil rights? The 287(g) program is a broken, racist relic of the past; it must be ended.

Published April 27, 2022 at 02:25AM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/JpoiM5P

ACLU: ICE Program Foments Abuse, Hatred, and Fear — and Makes Us All Less Safe

In 2017, Gerardo Martinez-Morales was driving to the doctor’s office when he was pulled over by sheriff’s deputies in Galveston County, Tex.. One week later, the father of four and grandfather of three who lived in the U.S. for more than two decades was deported to Mexico. The reason given for the traffic stop that caused him to be torn from his family of U.S. citizens? A broken taillight.

Under Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) 287(g) program, such travesties are all too common. The 287(g) program — named after a section of the 1996 Immigration and Nationality Act — sounds wonky, but is relatively simple and terribly life-altering in practice: It allows local law enforcement agencies, primarily sheriffs, to carry out certain duties normally reserved for federal ICE agents, such as investigating a person’s immigration status and holding people for transfer to ICE detention. The result is that even the most minor of interactions with local law enforcement can lead to detention, deportation, and separation from their families.

In a new research report, the ACLU found that dozens of sheriff partners in the 287(g) program have records of racism, abuse, and violence. Our analysis reveals that the majority of local partners have documented incidents of civil rights violations and other abuses. Our report makes clear that xenophobia is at the very heart of the program, which expanded five-fold under the anti-immigrant efforts of the Trump administration.

President Biden has continued to partner with sheriffs who entered into agreements with the Trump administration, despite promising to end them, and even though these partnerships undermine his administration’s stated priorities for criminal justice reform and immigrants’ rights.

https://infogram.com/1p6kvpjq2jerjza5gdx6qr5xq2c3rj5wjjv?live

While 287(g) is intended to be narrow in scope and proponents portray it as oriented towards deporting “criminals,” in practice, many sheriffs and their deputies wield their federally-delegated authorities quite widely. For years, local immigrant rights activists have documented racial profiling endemic to the program: sheriff’s deputies who look for any excuse to initially detain somebody they suspect of having a questionable immigration status — to funnel them into deportation.

Would Gerardo Martinez-Morales have been arrested for a “broken taillight” if he weren’t brown-skinned in an overwhelmingly white county policed by a sheriff who had pursued a 287(g) agreement and spoken publicly about the need to punish undocumented immigrants? Would the sheriff have pursued a 287(g) agreement in the first place if he weren’t on a mission to target immigrants?

After all, joining the program is voluntary under federal law and comes at local taxpayer expense with no measurable benefits. Studies suggest 287(g) undermines both public safety and public health as trust in local agencies plummets and fear rises. To better understand why a sheriff would still pursue a 287(g) agreement, it helps to look at the history of the program.

Nearly two-thirds of 287(g) partners have records of racial profiling and other civil rights abuses.

When Obama’s presidency ended, there were 34 remaining 287(g) agreements nationwide following several racial profiling investigations by the Department of Justice, including one that led to the termination of the 287(g) agreement in Alamance County, North Carolina. The Alamance County sheriff demanded deputies “bring me some Mexicans.” This led to incidents like that of a Latinx man who was arrested and later deported for “providing the wrong address for the crime scene” after he suffered a gunshot wound, or a Latinx women whose three young children were left alone for eight hours on the side of the highway at night after she was arrested and then deported for driving without a license.

Under the Trump administration, the program grew nearly five-fold in a few short years, reaching an all-time high of 152 participating agencies. Among the new agreements was one with the same sheriff in Alamance County.

This is no coincidence. Our investigation shows that the Trump administration actively recruited sheriffs to join the 287(g) program as part of the administration’s larger anti-immigrant agenda, and at the expense of civil rights.

As the ACLU report makes clear, xenophobia and rights abuses run rampant in the program. We find that 59 percent of 287(g) sheriffs have records of anti-immigrant rhetoric, and over half have expressly advocated inhumane federal immigration policies, in some cases while vowing to disobey any federal directives they disagree with. Nearly two-thirds of 287(g) partners have records of racial profiling and other civil rights abuses, while more than three-quarters operate detention facilities with documented patterns of abuse and inhumane conditions.

https://infogram.com/1pl63752m5zp9zfqmj1nwwmqz0f3k7721v?live

With a record this abysmal, there is no salvaging 287(g). As a candidate, President Biden pledged to “aggressively limit” 287(g), including by terminating all agreements entered under the Trump administration. But over a year into his administration, he has only ended one agreement.

Will President Biden make good on this promise to disentangle federal immigration enforcement from the everyday work of local law enforcement officers? Or will he continue to work with the very officials who perpetrate abuses, target immigrant communities, and undermine civil rights? The 287(g) program is a broken, racist relic of the past; it must be ended.

Published April 26, 2022 at 09:55PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/JpoiM5P

Tuesday 26 April 2022

ACLU: Mississippi Voters Are Fighting for Fair Representation on the State’s Highest Court

Black voters in Mississippi deserve full and fair opportunities for representation at the highest level. And the next generation of Black lawyers and civic leaders deserve full and fair opportunities to serve at the highest level. That must include the opportunity to become a justice of the Mississippi Supreme Court. It’s far past time that the Supreme Court districts that Mississippi uses to elect its Supreme Court reflect the diversity of the state’s population, rather than diminishing the voice of Black voters. That’s why the ACLU and ACLU of Mississippi, along with our co-counsel, have filed a lawsuit in federal court on behalf of Black civic leaders challenging Mississippi’s Supreme Court districts.

Mississippi’s population is almost 40 percent Black — a greater proportion than any other state in the nation. Yet in the entire history of Mississippi, there have been a total of only four Black justices on the state’s nine-member Supreme Court. In fact, there has never been more than one Black justice on that court at any given time. The last time a Black justice was elected to the Mississippi Supreme Court in a contested election was in 2004, nearly 20 years ago. The reason for this gross inequality is that Mississippi employs Supreme Court district boundaries that dilute the voting strength of Black Mississippians in state Supreme Court elections. The challenged districts violate the Voting Rights Act and the U.S. Constitution. Mississippi must do better.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act makes it illegal for states to draw district lines that water down the voting strength of voters from minority racial groups. That is exactly what Mississippi’s Supreme Court election district lines do. Black voters comprise a majority of the population in certain regions of the state, such as the Mississippi Delta and the state capital of Jackson, but Black voters do not comprise a majority in any of the three Supreme Court districts as currently drawn.

Moreover, voting is heavily polarized on the basis of race across Mississippi. That high degree of polarization means that candidates chosen by Black voters are typically defeated by white bloc voting in the current Supreme Court districts. By splitting Black voters across the three Supreme Court districts in a way that doesn’t allow them to be the majority in any of those districts, the challenged scheme provides Black voters with little opportunity (and certainly not an equal opportunity) to elect candidates of choice to the state Supreme Court. That is classic vote dilution.

Additionally, Mississippi’s Supreme Court districts are unconstitutional. These districts have not been changed since 1987 — before some of the plaintiffs in our case were even born. Indeed, they are not very different from districts used by Mississippi in the 1930s and 1940s during the era of Jim Crow. Also, Mississippi does not appear to have ever precleared the districts (that is, obtained approval from the Department of Justice or a federal court) as it was required to do under the Voting Rights Act. It passed them even though Black lawmakers strongly objected. The state and its policymakers cannot help but see the discriminatory, vote dilutive effects of those districts. These and other unusual circumstances show that racial discrimination was and is a motivating factor in the state’s persistent maintenance of these vote dilutive districts. Such improper motivations violate the Constitution.

Thankfully, the remedy to these violations of law is simple: Draw new district lines for the first time since 1987. In fact, only modest changes to the district lines for the state’s Supreme Court districts would be sufficient to make Supreme Court District 1 majority-Black and to provide Black voters with the opportunity to elect candidates of their choice. This change would also keep the state’s overall districting scheme for Supreme Court elections intact, while also ensuring that those elections comply with federal law and allow Black Mississippians an opportunity to elect candidates of choice.

Black Mississippians should not have to participate in critical elections on a grossly uneven playing field. That is wrong and erodes the trust so many people have in our democracy and our public institutions. In contrast, fair representation and multi-racial democracy shore up the integrity of our institutions and benefit all Mississippians.

This case is about Mississippi’s future — about whether the next generation of Black lawyers and civic leaders in Mississippi will have fully equal opportunities to obtain representation and to serve at the highest level, including as a justice of the Mississippi Supreme Court. Mississippi should redraw its Supreme Court district lines now. Federal law requires nothing less.

Published April 26, 2022 at 10:16PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/snLDOu2

ACLU: Mississippi Voters Are Fighting for Fair Representation on the State’s Highest Court

Black voters in Mississippi deserve full and fair opportunities for representation at the highest level. And the next generation of Black lawyers and civic leaders deserve full and fair opportunities to serve at the highest level. That must include the opportunity to become a justice of the Mississippi Supreme Court. It’s far past time that the Supreme Court districts that Mississippi uses to elect its Supreme Court reflect the diversity of the state’s population, rather than diminishing the voice of Black voters. That’s why the ACLU and ACLU of Mississippi, along with our co-counsel, have filed a lawsuit in federal court on behalf of Black civic leaders challenging Mississippi’s Supreme Court districts.

Mississippi’s population is almost 40 percent Black — a greater proportion than any other state in the nation. Yet in the entire history of Mississippi, there have been a total of only four Black justices on the state’s nine-member Supreme Court. In fact, there has never been more than one Black justice on that court at any given time. The last time a Black justice was elected to the Mississippi Supreme Court in a contested election was in 2004, nearly 20 years ago. The reason for this gross inequality is that Mississippi employs Supreme Court district boundaries that dilute the voting strength of Black Mississippians in state Supreme Court elections. The challenged districts violate the Voting Rights Act and the U.S. Constitution. Mississippi must do better.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act makes it illegal for states to draw district lines that water down the voting strength of voters from minority racial groups. That is exactly what Mississippi’s Supreme Court election district lines do. Black voters comprise a majority of the population in certain regions of the state, such as the Mississippi Delta and the state capital of Jackson, but Black voters do not comprise a majority in any of the three Supreme Court districts as currently drawn.

Moreover, voting is heavily polarized on the basis of race across Mississippi. That high degree of polarization means that candidates chosen by Black voters are typically defeated by white bloc voting in the current Supreme Court districts. By splitting Black voters across the three Supreme Court districts in a way that doesn’t allow them to be the majority in any of those districts, the challenged scheme provides Black voters with little opportunity (and certainly not an equal opportunity) to elect candidates of choice to the state Supreme Court. That is classic vote dilution.

Additionally, Mississippi’s Supreme Court districts are unconstitutional. These districts have not been changed since 1987 — before some of the plaintiffs in our case were even born. Indeed, they are not very different from districts used by Mississippi in the 1930s and 1940s during the era of Jim Crow. Also, Mississippi does not appear to have ever precleared the districts (that is, obtained approval from the Department of Justice or a federal court) as it was required to do under the Voting Rights Act. It passed them even though Black lawmakers strongly objected. The state and its policymakers cannot help but see the discriminatory, vote dilutive effects of those districts. These and other unusual circumstances show that racial discrimination was and is a motivating factor in the state’s persistent maintenance of these vote dilutive districts. Such improper motivations violate the Constitution.

Thankfully, the remedy to these violations of law is simple: Draw new district lines for the first time since 1987. In fact, only modest changes to the district lines for the state’s Supreme Court districts would be sufficient to make Supreme Court District 1 majority-Black and to provide Black voters with the opportunity to elect candidates of their choice. This change would also keep the state’s overall districting scheme for Supreme Court elections intact, while also ensuring that those elections comply with federal law and allow Black Mississippians an opportunity to elect candidates of choice.

Black Mississippians should not have to participate in critical elections on a grossly uneven playing field. That is wrong and erodes the trust so many people have in our democracy and our public institutions. In contrast, fair representation and multi-racial democracy shore up the integrity of our institutions and benefit all Mississippians.

This case is about Mississippi’s future — about whether the next generation of Black lawyers and civic leaders in Mississippi will have fully equal opportunities to obtain representation and to serve at the highest level, including as a justice of the Mississippi Supreme Court. Mississippi should redraw its Supreme Court district lines now. Federal law requires nothing less.

Published April 26, 2022 at 05:46PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/snLDOu2

Monday 25 April 2022

ACLU: Trump’s Remain in Mexico policy is at the Supreme Court. Here’s what is at stake.

This week the Supreme Court will hear a case that could entrench the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy, which forces people seeking asylum to await their court dates in dangerous conditions in Mexico. The Remain in Mexico Policy, misleadingly dubbed the “Migrant Protection Protocols” created a humanitarian disaster at the border and has been the subject of ACLU lawsuits since it was first implemented in 2019.

President Biden made a campaign promise to end Remain in Mexico, recognizing the grave harm it subjects people seeking asylum to. Biden followed through on his promise and terminated the policy. But Texas and Missouri sued, and a federal Texas district court judge ordered the federal government to restart the program.

The Biden administration has tried multiple times to end the policy, including by asking the U.S. Supreme Court to block the order on an emergency basis – a move the ACLU supported in an amicus brief – but the Court declined to do so. The Biden administration has been forced to resume the policy while litigation continues.

Biden v. Trump has now made its way up to the Supreme Court to be heard on the merits. Here is what’s at stake.

The ability of a president to undo the policies of a former administration

The lower court decision under review by the Supreme Court would effectively keep the Trump administration’s shameful Remain in Mexico policy in place indefinitely, even though the policy did not exist under multiple administrations (including the Trump Administration before 2019).

This decision is contrary to a fundamental principle of a democracy: A new administration, selected by the people, should be empowered to reject its predecessor’s policies and adopt those it believes are in the public interest. The government is, of course, constrained by statutes, including the requirement to provide reasoning for its policy decisions. But by upending the normal rules that govern agency decisions and unjustifiably locking in Trump’s policy, the lower court overstepped its role as a neutral enforcer of the rules.

The anti-democratic implications of that holding are deeply troubling, and the Supreme Court must reject it.

Whether the government is required to detain all asylum seekers

In ordering the Biden administration to resume the Remain in Mexico policy, the lower courts held that immigration law limits the federal government to only two options when people seek asylum at the border: detain them or forcibly return them to Mexico before their hearing. Since the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) lacks capacity to detain all people seeking asylum, the judge reasoned that the only choice would be to send them to Mexico while their cases proceed.

This is a patently false choice. Congress has stipulated that DHS has broad power to avoid unnecessarily detaining people and to release people to their networks of care while their immigration cases proceed. In fact, all presidential administrations have exercised broad discretion to release people rather than restricting DHS to two binary choices – including the Trump administration itself.

The lives of asylum seekers

Most importantly, at stake is whether the U.S. will continue to be a country that allows people fleeing persecution to seek safety inside its borders. Remain in Mexico, and other related policies, like Title 42, which has shut down access to asylum at the southern border for over two years under the guise of public health, are attempts to dismantle longstanding U.S. asylum policy that uphold our commitment to international human rights norms.

During the two years the policy was in effect under Trump, Human Rights First documented over 1,540 reported cases of kidnappings, murder, torture, rape, and other forms of violence against asylum seekers returned to Mexico. U.S. and Mexican authorities have failed to establish adequate housing options or to provide access to medical care and work, leaving people vulnerable to transnational cartels who prey on migrants — particularly those who are Black or LGBTQ+.

If the Supreme Court prevents the Biden administration from ending Remain in Mexico, it will enshrine a new legacy for the United States – a legacy of turning its back on international commitments and sending people directly into harm’s way.

Published April 25, 2022 at 09:30PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/6ONWrfb

ACLU: Trump’s Remain in Mexico policy is at the Supreme Court. Here’s what is at stake.

This week the Supreme Court will hear a case that could entrench the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy, which forces people seeking asylum to await their court dates in dangerous conditions in Mexico. The Remain in Mexico Policy, misleadingly dubbed the “Migrant Protection Protocols” created a humanitarian disaster at the border and has been the subject of ACLU lawsuits since it was first implemented in 2019.

President Biden made a campaign promise to end Remain in Mexico, recognizing the grave harm it subjects people seeking asylum to. Biden followed through on his promise and terminated the policy. But Texas and Missouri sued, and a federal Texas district court judge ordered the federal government to restart the program.

The Biden administration has tried multiple times to end the policy, including by asking the U.S. Supreme Court to block the order on an emergency basis – a move the ACLU supported in an amicus brief – but the Court declined to do so. The Biden administration has been forced to resume the policy while litigation continues.

Biden v. Trump has now made its way up to the Supreme Court to be heard on the merits. Here is what’s at stake.

The ability of a president to undo the policies of a former administration

The lower court decision under review by the Supreme Court would effectively keep the Trump administration’s shameful Remain in Mexico policy in place indefinitely, even though the policy did not exist under multiple administrations (including the Trump Administration before 2019).

This decision is contrary to a fundamental principle of a democracy: A new administration, selected by the people, should be empowered to reject its predecessor’s policies and adopt those it believes are in the public interest. The government is, of course, constrained by statutes, including the requirement to provide reasoning for its policy decisions. But by upending the normal rules that govern agency decisions and unjustifiably locking in Trump’s policy, the lower court overstepped its role as a neutral enforcer of the rules.

The anti-democratic implications of that holding are deeply troubling, and the Supreme Court must reject it.

Whether the government is required to detain all asylum seekers

In ordering the Biden administration to resume the Remain in Mexico policy, the lower courts held that immigration law limits the federal government to only two options when people seek asylum at the border: detain them or forcibly return them to Mexico before their hearing. Since the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) lacks capacity to detain all people seeking asylum, the judge reasoned that the only choice would be to send them to Mexico while their cases proceed.

This is a patently false choice. Congress has stipulated that DHS has broad power to avoid unnecessarily detaining people and to release people to their networks of care while their immigration cases proceed. In fact, all presidential administrations have exercised broad discretion to release people rather than restricting DHS to two binary choices – including the Trump administration itself.

The lives of asylum seekers

Most importantly, at stake is whether the U.S. will continue to be a country that allows people fleeing persecution to seek safety inside its borders. Remain in Mexico, and other related policies, like Title 42, which has shut down access to asylum at the southern border for over two years under the guise of public health, are attempts to dismantle longstanding U.S. asylum policy that uphold our commitment to international human rights norms.

During the two years the policy was in effect under Trump, Human Rights First documented over 1,540 reported cases of kidnappings, murder, torture, rape, and other forms of violence against asylum seekers returned to Mexico. U.S. and Mexican authorities have failed to establish adequate housing options or to provide access to medical care and work, leaving people vulnerable to transnational cartels who prey on migrants — particularly those who are Black or LGBTQ+.

If the Supreme Court prevents the Biden administration from ending Remain in Mexico, it will enshrine a new legacy for the United States – a legacy of turning its back on international commitments and sending people directly into harm’s way.

Published April 25, 2022 at 05:00PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/6ONWrfb

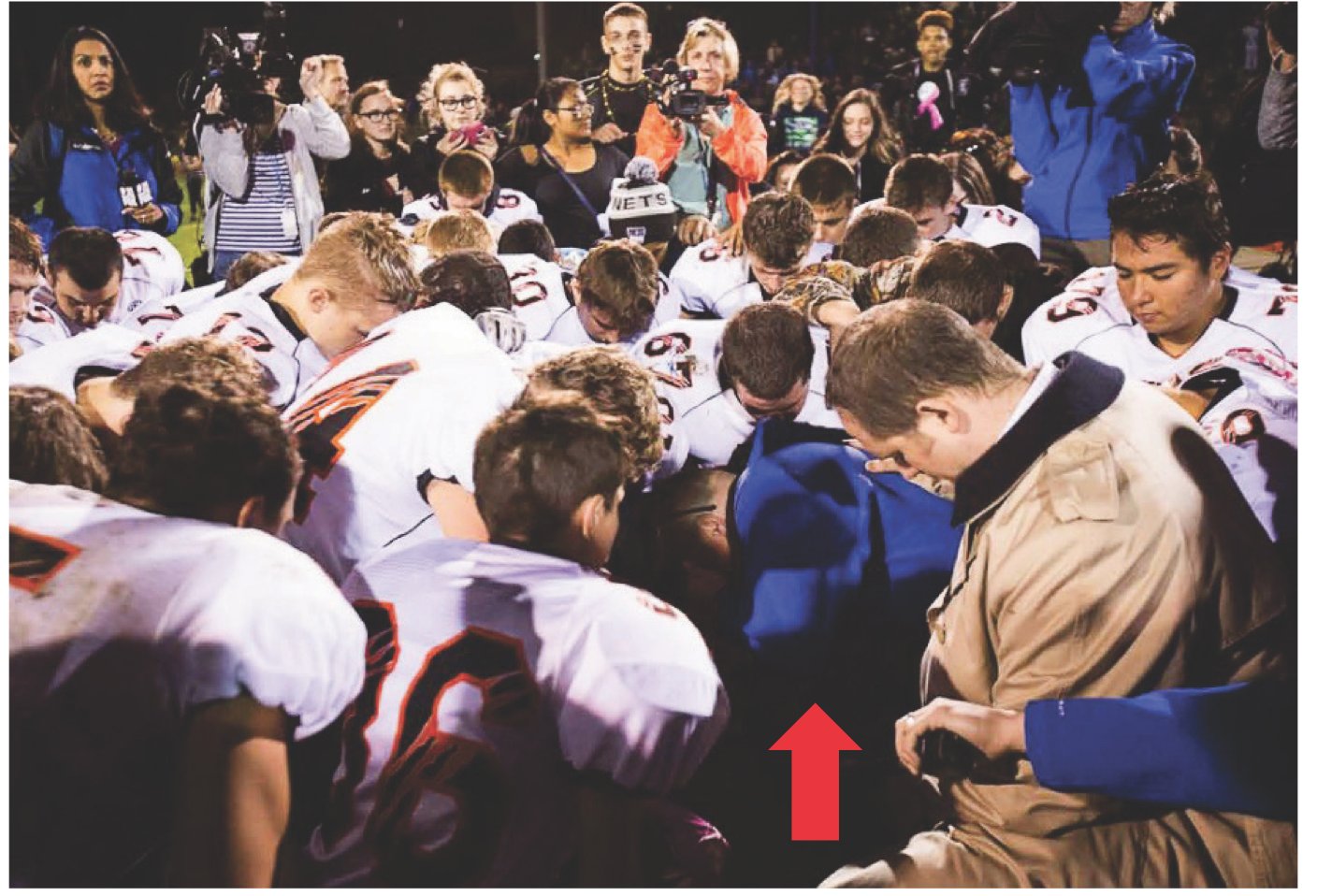

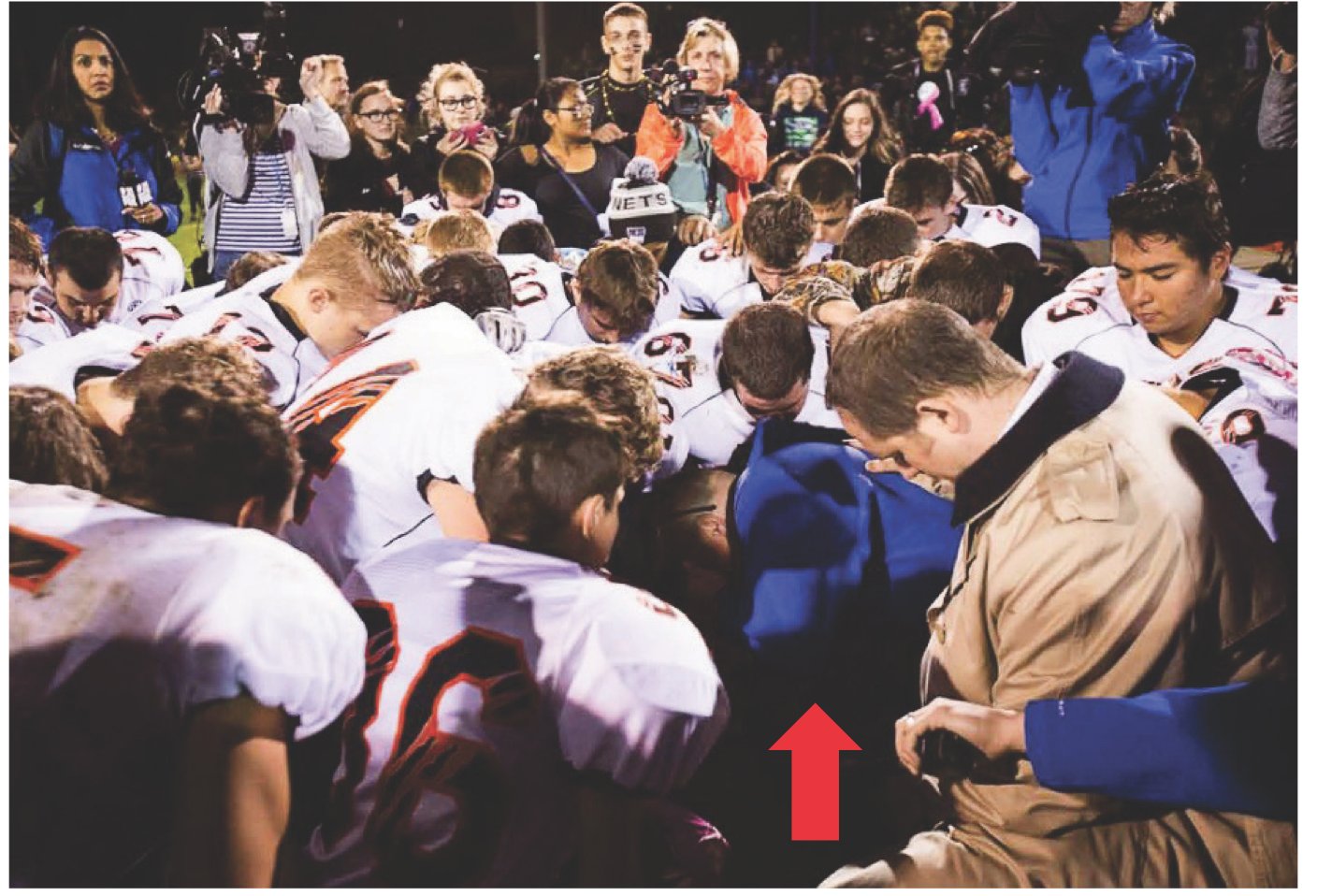

ACLU: The Supreme Court Must Protect Students From School-Sponsored Prayer | American Civil Liberties Union

On-duty public-school staff may not pray with students. Period. That’s been the law under the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause for more than half a century. Even the Trump administration—hardly a bastion of church-state separation—agreed, proclaiming in its school-prayer guidance that “school employees are prohibited by the First Amendment from encouraging or discouraging prayer, and from actively participating in such activity with students.” But that could soon change if the Supreme Court rules in favor of a public-school football coach who demanded the right to lead his players in prayer at the 50-yard-line at the end of each game.

This morning, the court is hearing oral arguments in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, in which Joseph Kennedy, a former high school football coach, claims that school officials in Bremerton, Washington violated his religious-exercise and free-speech rights by placing him on administrative leave for repeatedly leading on-field prayers with his team at the close of each football game.

The coach portrays the case as involving his right to personal, silent prayer. But as a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals judge pointed out in ruling against the coach, Kennedy and his attorneys have repeatedly misrepresented the facts of the case, spinning a “false” and “deceitful narrative.” In truth, the school offered — and Kennedy rejected — several religious accommodations that would have allowed him to engage in private, post-game prayer. Instead, he insisted on continuing his unconstitutional practice of praying with students.

The Supreme Court has long recognized that the separation of religion and government is especially important in our public schools, which must equally serve students of all faiths, and those of none. When public-school officials demonstrably favor some faiths over others or promote religious doctrine, it sends a message of exclusion to students who don’t follow the preferred faith. And students are especially vulnerable to coercion, both subtle and overt, when subjected to school-sponsored prayer or other official religious exercise.

Indeed, several of Coach Kennedy’s players participated in his prayers only because they felt pressured to do so. As one amicus brief — filed on behalf of former professional football players and former college athletes — explains, coaches wield great power and influence over their athletes. Many players are naturally inclined to view their coaches as authority figures and to obey their explicit and implicit commands. Athletes understandably seek the approval of their coaches, who control nearly all aspects of their participation and playing time. For some high school students, coaches may be instrumental in their ability to obtain collegiate athletic scholarships. Under the gaze of their coaches, fellow team members, the audience, and the media who gathered to cover Kennedy’s highly publicized prayer, few students would feel comfortable opting out of the post-game prayer huddle.

The ACLU strongly supports the free exercise of religion and free speech. Earlier this year, for example, we filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court, arguing that the City of Boston unconstitutionally denied a Christian group’s request to fly, for a single hour, a flag featuring a cross on a city flagpole. The city denied the request even though it had intentionally opened up the flagpole as a public forum and consistently allowed dozens of other groups to temporarily raise their flags. The flag in that case, we explained, was private speech and would be understood as such by the community, and therefore had to be accommodated.

Not so in Bremerton. Kennedy conceded that he delivered his prayers while he was on the job, explaining to the press that the prayers were, in his view, “helping these kids be better people.” Even if the school disclaims any endorsement, a student who witnesses the coach lead his team in prayer would still perceive it as bearing the school’s stamp of approval. And anyone familiar with the coach-athlete relationship would immediately understand just how coercive that practice is. In barring him from praying with students in this setting, while offering him many ways to pray privately, school officials did only what was required of them by the First Amendment: They protected students’ religious freedom by shielding them from school-sponsored religious exercise. Now, it’s the Supreme Court’s turn to do the same.

Published April 25, 2022 at 06:30PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/DXE50SK

ACLU: The Supreme Court Must Protect Students From School-Sponsored Prayer | American Civil Liberties Union

On-duty public-school staff may not pray with students. Period. That’s been the law under the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause for more than half a century. Even the Trump administration—hardly a bastion of church-state separation—agreed, proclaiming in its school-prayer guidance that “school employees are prohibited by the First Amendment from encouraging or discouraging prayer, and from actively participating in such activity with students.” But that could soon change if the Supreme Court rules in favor of a public-school football coach who demanded the right to lead his players in prayer at the 50-yard-line at the end of each game.

This morning, the court is hearing oral arguments in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, in which Joseph Kennedy, a former high school football coach, claims that school officials in Bremerton, Washington violated his religious-exercise and free-speech rights by placing him on administrative leave for repeatedly leading on-field prayers with his team at the close of each football game.

The coach portrays the case as involving his right to personal, silent prayer. But as a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals judge pointed out in ruling against the coach, Kennedy and his attorneys have repeatedly misrepresented the facts of the case, spinning a “false” and “deceitful narrative.” In truth, the school offered — and Kennedy rejected — several religious accommodations that would have allowed him to engage in private, post-game prayer. Instead, he insisted on continuing his unconstitutional practice of praying with students.

The Supreme Court has long recognized that the separation of religion and government is especially important in our public schools, which must equally serve students of all faiths, and those of none. When public-school officials demonstrably favor some faiths over others or promote religious doctrine, it sends a message of exclusion to students who don’t follow the preferred faith. And students are especially vulnerable to coercion, both subtle and overt, when subjected to school-sponsored prayer or other official religious exercise.

Indeed, several of Coach Kennedy’s players participated in his prayers only because they felt pressured to do so. As one amicus brief — filed on behalf of former professional football players and former college athletes — explains, coaches wield great power and influence over their athletes. Many players are naturally inclined to view their coaches as authority figures and to obey their explicit and implicit commands. Athletes understandably seek the approval of their coaches, who control nearly all aspects of their participation and playing time. For some high school students, coaches may be instrumental in their ability to obtain collegiate athletic scholarships. Under the gaze of their coaches, fellow team members, the audience, and the media who gathered to cover Kennedy’s highly publicized prayer, few students would feel comfortable opting out of the post-game prayer huddle.

The ACLU strongly supports the free exercise of religion and free speech. Earlier this year, for example, we filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court, arguing that the City of Boston unconstitutionally denied a Christian group’s request to fly, for a single hour, a flag featuring a cross on a city flagpole. The city denied the request even though it had intentionally opened up the flagpole as a public forum and consistently allowed dozens of other groups to temporarily raise their flags. The flag in that case, we explained, was private speech and would be understood as such by the community, and therefore had to be accommodated.

Not so in Bremerton. Kennedy conceded that he delivered his prayers while he was on the job, explaining to the press that the prayers were, in his view, “helping these kids be better people.” Even if the school disclaims any endorsement, a student who witnesses the coach lead his team in prayer would still perceive it as bearing the school’s stamp of approval. And anyone familiar with the coach-athlete relationship would immediately understand just how coercive that practice is. In barring him from praying with students in this setting, while offering him many ways to pray privately, school officials did only what was required of them by the First Amendment: They protected students’ religious freedom by shielding them from school-sponsored religious exercise. Now, it’s the Supreme Court’s turn to do the same.

Published April 25, 2022 at 02:00PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/DXE50SK

Thursday 21 April 2022

ACLU: The Law & Order Reboot Could Not Come at a Worse Time for Criminal Law Reform

You might think you know a lot about the criminal justice system in America. Perhaps you have a vision of what happens at arrest, during police questioning, when bail is set, or during trial. You’ve heard the familiar Miranda warnings on TV and seen lawyers spouting objections in courtroom scenes. However, if you are like many people, whose views on the criminal legal process are primarily formed by TV and movies, you may have a woefully rosy picture of how accused people are treated in thousands of courtrooms across the country every day.

A huge culprit in misshaping Americans’ views of their local criminal legal systems is the hit show Law & Order, the longest-running law enforcement series on television, which is now back on air for its 21st season. While unquestionably a successful entertainment franchise, Law & Order and shows like it have done incredible damage to the fight for a truly fair and effective criminal justice system. This is because a vast segment of the American public is getting their information about the legal system from shows like Law & Order, and in many critically-important ways, the fiction of the show is nothing like reality.

For example, take bail. On TV, we watch people proceed swiftly to a real hearing following an arrest, in front of a judge, with a lawyer representing them. Arguments get made about whether the person poses a flight risk or an unmanageable danger to others if released. An individualized assessment is then made.

In reality, in much of the country, someone arrested and accused of a crime has their bail set without any hearing whatsoever: Bail is predetermined by charge without consideration of a person’s finances or other factors. Elsewhere, bail is set by a police officer, judge, or clerk behind closed doors. Even in places that hold some sort of bail hearing, the proceeding typically lasts only a few seconds, and people accused of crimes often have no lawyer to help them make arguments, preserve other rights (such as the right against self-incrimination), or to negotiate with the prosecutor. The result is a massive system of wealth-based and unjustified incarceration. This decision point influences the entire remainder of a person’s case, as those who cannot pay bail are incarcerated, separated from their families, left to prepare their defense from jail, and housed in often-abysmal, sometimes deadly conditions.

On TV, judges apply the law meticulously. In reality, many judges express overt bias, act rashly, and are condescending and cruel to criminal defendants. As a lawyer investigating practices on behalf of the ACLU, it is not uncommon for me to observe knee-jerk reactions from judges based on one element of the case, or to see judges show obvious preference to wealthier white defendants over low-income people of color. But members of the public rarely observe judges in action. When local and national journalism accurately covers judicial conduct, members of the public are often shocked by the way local judicial officers wield power.

On Law & Order, about 60 percent of cases go to trial. In reality, only about 2 percent of people have a criminal trial, largely because of the prevalent role of coercive plea bargaining, pressures of pretrial detention, and the lopsided balance of power between the prosecution and defense.

The perception driven by TV crime dramas that police are primarily investigating serious, violent crimes and are largely accurate in who they accuse is incredibly damaging. In reality, violent crimes only represent about 4 percent of law enforcement’s scope, and clearance rates — the number of reported crimes matched to an arrest — are under 50 percent for violent crimes and under 17 percent for property crimes.

Now, we are witnessing a misguided backlash to much-overdue criminal law reforms in America. Political opportunists are peddling suggestive, inaccurate narratives about crime, safety, and fairness. The truth is that harsh criminal law policies do not make communities safer, and reforms are not the reason for tragic instances of interpersonal violence. To understand why reforms that seek alternatives to incarceration continue to be desperately needed, it is essential that voters understand what their elected judges, prosecutors, and law enforcement chiefs actually do when they are entrusted to uphold the constitutional rights of everyone in the system.

In the meantime, it behooves the writers and producers of much-streamed shows to portray these issues with more nuance and accuracy — including by hiring defense attorneys and formerly-incarcerated people, and not just prosecutors and cops to consult in their writers’ rooms. Creators of TV crime dramas must recognize and take responsibility for the tremendous impact they have on the way jurors and voters perceive our justice system.

Published April 21, 2022 at 11:55PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/rJDtzCc

ACLU: The Law & Order Reboot Could Not Come at a Worse Time for Criminal Law Reform

You might think you know a lot about the criminal justice system in America. Perhaps you have a vision of what happens at arrest, during police questioning, when bail is set, or during trial. You’ve heard the familiar Miranda warnings on TV and seen lawyers spouting objections in courtroom scenes. However, if you are like many people, whose views on the criminal legal process are primarily formed by TV and movies, you may have a woefully rosy picture of how accused people are treated in thousands of courtrooms across the country every day.

A huge culprit in misshaping Americans’ views of their local criminal legal systems is the hit show Law & Order, the longest-running law enforcement series on television, which is now back on air for its 21st season. While unquestionably a successful entertainment franchise, Law & Order and shows like it have done incredible damage to the fight for a truly fair and effective criminal justice system. This is because a vast segment of the American public is getting their information about the legal system from shows like Law & Order, and in many critically-important ways, the fiction of the show is nothing like reality.

For example, take bail. On TV, we watch people proceed swiftly to a real hearing following an arrest, in front of a judge, with a lawyer representing them. Arguments get made about whether the person poses a flight risk or an unmanageable danger to others if released. An individualized assessment is then made.

In reality, in much of the country, someone arrested and accused of a crime has their bail set without any hearing whatsoever: Bail is predetermined by charge without consideration of a person’s finances or other factors. Elsewhere, bail is set by a police officer, judge, or clerk behind closed doors. Even in places that hold some sort of bail hearing, the proceeding typically lasts only a few seconds, and people accused of crimes often have no lawyer to help them make arguments, preserve other rights (such as the right against self-incrimination), or to negotiate with the prosecutor. The result is a massive system of wealth-based and unjustified incarceration. This decision point influences the entire remainder of a person’s case, as those who cannot pay bail are incarcerated, separated from their families, left to prepare their defense from jail, and housed in often-abysmal, sometimes deadly conditions.

On TV, judges apply the law meticulously. In reality, many judges express overt bias, act rashly, and are condescending and cruel to criminal defendants. As a lawyer investigating practices on behalf of the ACLU, it is not uncommon for me to observe knee-jerk reactions from judges based on one element of the case, or to see judges show obvious preference to wealthier white defendants over low-income people of color. But members of the public rarely observe judges in action. When local and national journalism accurately covers judicial conduct, members of the public are often shocked by the way local judicial officers wield power.

On Law & Order, about 60 percent of cases go to trial. In reality, only about 2 percent of people have a criminal trial, largely because of the prevalent role of coercive plea bargaining, pressures of pretrial detention, and the lopsided balance of power between the prosecution and defense.

The perception driven by TV crime dramas that police are primarily investigating serious, violent crimes and are largely accurate in who they accuse is incredibly damaging. In reality, violent crimes only represent about 4 percent of law enforcement’s scope, and clearance rates — the number of reported crimes matched to an arrest — are under 50 percent for violent crimes and under 17 percent for property crimes.

Now, we are witnessing a misguided backlash to much-overdue criminal law reforms in America. Political opportunists are peddling suggestive, inaccurate narratives about crime, safety, and fairness. The truth is that harsh criminal law policies do not make communities safer, and reforms are not the reason for tragic instances of interpersonal violence. To understand why reforms that seek alternatives to incarceration continue to be desperately needed, it is essential that voters understand what their elected judges, prosecutors, and law enforcement chiefs actually do when they are entrusted to uphold the constitutional rights of everyone in the system.

In the meantime, it behooves the writers and producers of much-streamed shows to portray these issues with more nuance and accuracy — including by hiring defense attorneys and formerly-incarcerated people, and not just prosecutors and cops to consult in their writers’ rooms. Creators of TV crime dramas must recognize and take responsibility for the tremendous impact they have on the way jurors and voters perceive our justice system.

Published April 21, 2022 at 07:25PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/rJDtzCc

ACLU: Documents Reveal Confusion and Lack of Training in Texas Execution

As Texas seeks to execute Carl Buntion today and Melissa Lucio next week, it is worth reflecting on the grave and irreversible failures that occurred when the state executed Quintin Jones on May 19, 2021. For the first time in its history — and in violation of a federal court’s directive and the Texas Administrative Code — Texas excluded the media from witnessing the state’s execution of Quintin Jones. In the months that followed, Texas executed two additional people without providing any assurance that the underlying dysfunction causing errors at Mr. Jones’ execution were addressed. This is particularly concerning given that Texas has executed far more people than any other state and has botched numerous executions.

The First Amendment guarantees the public and the press have a right to observe executions. Media access to executions is a critical form of public oversight as the government exerts its power to end a human life. Consistent with Texas policy, two reporters travelled to the Huntsville Unit, where executions take place, to witness the execution of Mr. Jones in May 2021. The reporters waited across the street from the execution chamber, but Texas inexplicably excluded them from witnessing the execution.

Immediately after this fundamental and unconstitutional breakdown in procedure, Texas vowed to investigate what went wrong. The investigation resulted in the issuance of a perfunctory statement asserting without evidence that “extensive training” was conducted prior to the execution, but that issues still occurred. In June 2021, the ACLU submitted a request under the Texas Public Information Act for documents related to the errors at Mr. Jones’ execution and the investigation that followed. After six months of stonewalling during which time Texas executed two more people, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) released troubling new documents. These documents reveal a department woefully unprepared to carry out an execution, due to confusion and lack of training.

The documents describe interviews with staff who reported “a lot of unwritten procedures,” confusion about whether there were any written guidelines or protocols about executions, a lack of a “clear understanding of [their] role,” and staff who were “not trained.” An interview with one individual who appears to have participated in previous executions revealed that “to [his] knowledge, there are no written guidelines/protocols about the execution itself. He is aware of a document titled Execution Procedure-April 2021, however he stated he has not read it thoroughly.” Multiple documents describe a picture of confusion as a result of “all the changes,” including changes in the execution process. Taken together, these documents reveal a global lack of understanding about execution procedures generally.

The documents, which TDCJ tried for months to withhold, make clear that the department is not prepared to carry out another execution in line with Texas policy or the Constitution. While excluding media from an execution is easily noticeable, other errors may be less apparent. When the state makes a mistake in executing a person, those mistakes are unfixable and inexcusable. There is no room for error when the final moments of a person’s life are on the line.

There are countless reasons to oppose executions: the failure to protect innocent lives, the systemic racial bias in the application of the death penalty, and prosecutorial misconduct in capital cases are just a few examples. Mr. Buntion, scheduled to be executed today, is 78-years-old and has medical vulnerabilities. Ms. Lucio, scheduled to be executed next week, has a strong case for her innocence and has the support of her surviving children. The TDCJ should not move forward with these executions. Texas’ mismanagement in carrying out past executions is yet another reason the state should abandon the cruel practice of capital punishment.

Published April 21, 2022 at 11:12PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/pinevgD

ACLU: Documents Reveal Confusion and Lack of Training in Texas Execution

As Texas seeks to execute Carl Buntion today and Melissa Lucio next week, it is worth reflecting on the grave and irreversible failures that occurred when the state executed Quintin Jones on May 19, 2021. For the first time in its history — and in violation of a federal court’s directive and the Texas Administrative Code — Texas excluded the media from witnessing the state’s execution of Quintin Jones. In the months that followed, Texas executed two additional people without providing any assurance that the underlying dysfunction causing errors at Mr. Jones’ execution were addressed. This is particularly concerning given that Texas has executed far more people than any other state and has botched numerous executions.

The First Amendment guarantees the public and the press have a right to observe executions. Media access to executions is a critical form of public oversight as the government exerts its power to end a human life. Consistent with Texas policy, two reporters travelled to the Huntsville Unit, where executions take place, to witness the execution of Mr. Jones in May 2021. The reporters waited across the street from the execution chamber, but Texas inexplicably excluded them from witnessing the execution.

Immediately after this fundamental and unconstitutional breakdown in procedure, Texas vowed to investigate what went wrong. The investigation resulted in the issuance of a perfunctory statement asserting without evidence that “extensive training” was conducted prior to the execution, but that issues still occurred. In June 2021, the ACLU submitted a request under the Texas Public Information Act for documents related to the errors at Mr. Jones’ execution and the investigation that followed. After six months of stonewalling during which time Texas executed two more people, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) released troubling new documents. These documents reveal a department woefully unprepared to carry out an execution, due to confusion and lack of training.

The documents describe interviews with staff who reported “a lot of unwritten procedures,” confusion about whether there were any written guidelines or protocols about executions, a lack of a “clear understanding of [their] role,” and staff who were “not trained.” An interview with one individual who appears to have participated in previous executions revealed that “to [his] knowledge, there are no written guidelines/protocols about the execution itself. He is aware of a document titled Execution Procedure-April 2021, however he stated he has not read it thoroughly.” Multiple documents describe a picture of confusion as a result of “all the changes,” including changes in the execution process. Taken together, these documents reveal a global lack of understanding about execution procedures generally.

The documents, which TDCJ tried for months to withhold, make clear that the department is not prepared to carry out another execution in line with Texas policy or the Constitution. While excluding media from an execution is easily noticeable, other errors may be less apparent. When the state makes a mistake in executing a person, those mistakes are unfixable and inexcusable. There is no room for error when the final moments of a person’s life are on the line.

There are countless reasons to oppose executions: the failure to protect innocent lives, the systemic racial bias in the application of the death penalty, and prosecutorial misconduct in capital cases are just a few examples. Mr. Buntion, scheduled to be executed today, is 78-years-old and has medical vulnerabilities. Ms. Lucio, scheduled to be executed next week, has a strong case for her innocence and has the support of her surviving children. The TDCJ should not move forward with these executions. Texas’ mismanagement in carrying out past executions is yet another reason the state should abandon the cruel practice of capital punishment.

Published April 21, 2022 at 06:42PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/pinevgD

Monday 18 April 2022

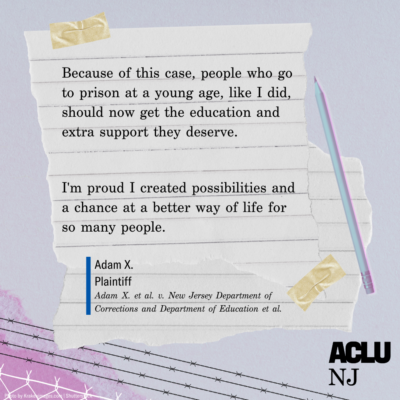

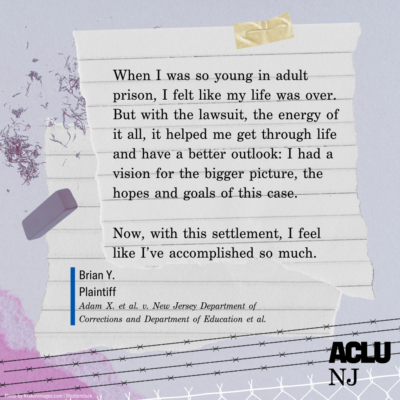

ACLU: A Student’s Journey: Fighting for Education Rights While in Prison

Young people with disabilities have a legal right to a free and appropriate public education, even when they are incarcerated. But for years, the educational needs of high school students in New Jersey’s state prisons were not being met.

That’s changing now, and Brian Y. is a big reason why.

Brian Y. entered state prison before he turned 18. He knew he had a right to an education inside, and he knew that as a student with disabilities, he was entitled to special education and related services.

He also knew his rights were being violated. So he took action.

The lawsuit, Adam X. et al. v. New Jersey Department of Corrections and Department of Education et al., was initiated five years ago by three students — Adam X., Brian Y., and Casey Z. (pseudonyms) — who alleged they were denied special education in prison. Thanks to their calls for change, the students’ legal team, including the ACLU of New Jersey Foundation, Disability Rights Advocates, and Proskauer Rose LLP, spent years investigating and litigating the case, which was certified by the federal District Court for the District of New Jersey as a class action in July 2021.

Their work was rewarded: On March 3, 2022, the District Court granted final approval of a settlement agreement that will usher in new policies to guarantee that students with disabilities in New Jersey prisons receive the special education and related services they are entitled to. The settlement also provides opportunities for make-up services and funds for those who were deprived special education in prison in the past, and ensures meaningful implementation of the new policies through a five-year monitoring plan.

Estimates suggest over 400 people may be impacted by the settlement — Brian Y. himself will receive $32,000 in compensatory education funds as part of the agreement.

We spoke with Brian Y., now 24 years old, about his education in prison and how his action resulted in a landmark settlement that will change the lives of young people denied services in prison. He talked about the experience in his own words.

This interview, which originally appeared on the ACLU of New Jersey’s blog, has been edited for clarity.

ACLU-NJ: What made you decide to take action to get an equal education?

Brian Y: I knew from my time in regular school that what was happening wasn’t normal. But all of this was my first time in jail or prison, so I thought that it was the norm: A tenth grader and a seventh grader all in the same class.

I was getting frustrated. I’d think to myself: “How is it that we have a teacher who doesn’t know the answer to certain questions?”

I brought this up with [an advocate]. They were shocked. So, they introduced me to the ACLU-NJ. And from there, the doors opened.

ACLU-NJ: What were the school materials you had like?

Brian Y: We didn’t even have textbooks. They had been recycled for years and were so outdated. The majority of the whole prison was working on the same lessons because it was the only thing they had available.

The teachers are supposed to be there for us, to teach us, but it was a jail mindset, just babysitting — they’d slide worksheets under the door.

ACLU-NJ: When you were in administrative segregation, you received instruction in a literal cage. What was it like to be educated in an environment like that?

Brian Y: I was so young. I don’t even know how to describe it. I felt like an animal.

I’m sitting in a room right now looking at a square table. Now, imagine us in a room. It’s you and the table, and everything around you is three stories high. Everyone is looking down at you.

And you’re in the middle, with lights on you, and a cage all around you. People outside are screaming and yelling. You’re trying to focus — but how can you? You can’t focus.

I remember being in the cage constantly jumping from the sounds. You could put your hand down and unintentionally make a loud noise. You’d hear people folding and stepping on the milk and juice cartons to make popping sounds. You would hear the metal keys. Everything was a loud noise. It was painful. It’s unreal, still thinking about it now. It was sad.

ACLU-NJ: What are your thoughts about missing out on educational services that you should have received?

Brian Y: The seven years I spent in the Department of Corrections, I was cheated out of education, and not learning the things I would have been if I was getting the right education. It’s going to have a huge impact on my life. You know everyone tells you, “Pay attention in school, you’re going to need it.” And here I am now saying the same thing.

ACLU-NJ: You were critical to the development of this case. What was it like to help your lawyers develop the complaint and prepare the suit?

Brian Y: It was exciting being a part of the lawsuit. It was unbelievable. It was like out of a movie. I was like an undercover lawyer. I’d ask questions in the classroom to find out what kinds of services other students were getting — or really, what services they weren’t.

Imagine being locked up at that age and having another inmate coming up to you and asking: “Do you have an IEP? What grade are you in? Why are you doing the same packet I’m doing? Do you get extra tutoring?”

A lot of the work I did to investigate took place when I was put in solitary confinement, taking notes on whatever small pieces of paper I had so I could use them later. Even helping other inmates to fill out forms for legal help: if they couldn’t mail it out themselves, I would put a stamp on it and make sure it got out.

Everyone I talked to or interviewed had a different story, and I was excited to see what impact they could have. It was a challenge for me — to see what I could uncover, or what role the next person I could get involved would have.

ACLU-NJ: After feeling like your concerns were ignored for so long, what was it like after you and your lawyers initiated the suit?

Brian Y: It felt amazing. Like 21 Jump Street, where an investigation blows up, and you laugh about it afterward.

I knew first when the lawsuit was announced and it was covered in the news, because all the teachers started finding out and losing their mind.

Deep down inside, I’m like, “I’m the man, I did this work. I made it happen!” I felt very overwhelmed and joyful.

ACLU-NJ: What did it feel like when you signed the settlement agreement, with your signature on the same document as the Department of Corrections commissioner?

Brian Y: Since getting out, I became a business owner. But signing my name to the changes the Department of Corrections would make felt even more powerful than turning the key to my shop for the first time.

There are so many people inside who have been there for years but didn’t have a way to change anything. Being so young and managing to make the change that we did is amazing.

ACLU-NJ: What differences do you think we’ll see from before the settlement and after?

Brian Y: That’s a good question. And a scary question.

With the settlement and the changes that are coming, there will be new requirements, a monitor to make sure they’re carried out, and all that. It’s scary, because there’s so much that needs to be done. Even when the lawsuit first broke — a lot of people weren’t ready for it.

But it’s good. Because you’re going to see the teachers who want to help, the ones who love education — they’re the ones who are going to stay. Those are the folks going to their boss saying, “We’re not doing enough to teach people.”

For the inmates who want to turn their lives around, they’re going to love this. There are so many people who want to learn but we were limited. The hope is for this lawsuit to lift those barriers. We weren’t getting special education services, let alone basic education or vocational training that we wanted. After this, things will hopefully change to give people the tools we need to be successful.

ACLU-NJ: How does it feel now, knowing you were a teenager when you started down this journey?

Brian Y: When I was so young in adult prison, I felt like my life was over. But with the lawsuit, the energy of it all, it helped me get through life and have a better outlook: I had a vision for the bigger picture, the hopes and goals of this case. Now, with this settlement, I feel like I’ve accomplished so much.

Knowing you’re the reason so many students in this predicament are going to have so much opportunity: It definitely means a lot. Especially coming from the bottom — coming up in a troubled environment, with early run-ins — making your voice heard and having a voice means a lot.

When I talk about it, it means so much to me, I really hold back tears. Sometimes I think to myself, “How did I get through it?” To deal with all of it, to become more powerful, to make change like that — it’s so good. Even with the mistakes I made in life, I feel good about who I truly am.

Coming from all the way from the beginning of this case, to now standing up and shouting — having a voice! shouting! — it means a lot. I try to laugh a lot. As I’m talking about it, it really means a lot to me. And the laughing is really holding back tears.

ACLU-NJ: What does it mean to know that you made it possible for people to get an education closer to the one they deserve?

Brian Y: To me this means my voice was heard. And for the other students in the class action, our voices were heard. Luckily, I was able to initiate positive change. I know this is going to break barriers, and it’s going to continue moving in the right direction, and this is just the start.

And I know there are teachers in there who want to do real lesson plans, want to really teach. I feel like I made a difference not just for students who want to learn but also for teachers who didn’t have a voice and wanted to teach.

ACLU-NJ: The settlement gives you and others in your circumstances opportunities to pursue education and training to compensate for what you were denied. What does that mean to you personally?

Brian Y: The compensatory education funds mean a lot. I had never had that help, but I’m being helped now. It’s kind of late, in terms of the Department of Corrections trying to make up for an education that we missed at such an important age, but I feel incredibly proud to finally have these opportunities and to know I was part of that. The people who care about me encourage me to stick with my passion, so I never gave up. I was even contacting technical colleges.

But when we first talked about the settlement, more than the comp ed, it was about the DOC changes for me — so other people didn’t have to go through what I did, so they can get proper education.

ACLU-NJ: Already more than 90 people have submitted compensatory education forms as part of the program created for class members. Are you proud of that?

Brian Y: Like I said — I like to challenge myself now because of the ACLU and everyone else. Ninety — that’s still short for us, because I know there’s a lot more than that who are eligible. This is just the beginning but we’re going to get there.

ACLU-NJ: Did you ever think about not taking action to fix things?

Brian Y: With this whole case, I could have just kept going with the flow, saying to myself this is normal. People could have said, “You’re in tenth grade doing seventh grade work – that’s all good, you’re guaranteed to pass.” But I couldn’t — it’s not right.

I never asked myself what if I didn’t get involved with the suit, because I’m so glad I did. But if I didn’t — it’d be the same now as it was then: A lot of people missing out on education. Every step of the way just made me want to fight harder, work more. We made our voices heard for ourselves and for other people who wanted to help. I was so committed, and I knew what was at stake.

ACLU-NJ: Five years later, what lessons do you take away from this?

Brian Y: From when we first started the class action to now — five years doesn’t feel like five years. But to get things done right, it takes time. To get it done right and to see real change. The investigation process, the manpower, everything, it was well due. Well due. I just roll with the punches. I know it’s not a simple change. This is a big, big change. It’s only right that it takes its time and goes through the process so we can get it RIGHT. We want it to be 100.

Class Members may continue to submit Compensatory Education Forms for up to two years. Although the notice period is complete, Class Members and their loved ones may still reach out to Class Counsel at prisoneducation@aclu-nj.org or prisoneducation@dralegal.org or by calling 973-854-1700.

Published April 18, 2022 at 08:58PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/MbTUHa2

ACLU: A Student’s Journey: Fighting for Education Rights While in Prison

Young people with disabilities have a legal right to a free and appropriate public education, even when they are incarcerated. But for years, the educational needs of high school students in New Jersey’s state prisons were not being met.

That’s changing now, and Brian Y. is a big reason why.

Brian Y. entered state prison before he turned 18. He knew he had a right to an education inside, and he knew that as a student with disabilities, he was entitled to special education and related services.

He also knew his rights were being violated. So he took action.

The lawsuit, Adam X. et al. v. New Jersey Department of Corrections and Department of Education et al., was initiated five years ago by three students — Adam X., Brian Y., and Casey Z. (pseudonyms) — who alleged they were denied special education in prison. Thanks to their calls for change, the students’ legal team, including the ACLU of New Jersey Foundation, Disability Rights Advocates, and Proskauer Rose LLP, spent years investigating and litigating the case, which was certified by the federal District Court for the District of New Jersey as a class action in July 2021.

Their work was rewarded: On March 3, 2022, the District Court granted final approval of a settlement agreement that will usher in new policies to guarantee that students with disabilities in New Jersey prisons receive the special education and related services they are entitled to. The settlement also provides opportunities for make-up services and funds for those who were deprived special education in prison in the past, and ensures meaningful implementation of the new policies through a five-year monitoring plan.

Estimates suggest over 400 people may be impacted by the settlement — Brian Y. himself will receive $32,000 in compensatory education funds as part of the agreement.

We spoke with Brian Y., now 24 years old, about his education in prison and how his action resulted in a landmark settlement that will change the lives of young people denied services in prison. He talked about the experience in his own words.

This interview, which originally appeared on the ACLU of New Jersey’s blog, has been edited for clarity.

ACLU-NJ: What made you decide to take action to get an equal education?

Brian Y: I knew from my time in regular school that what was happening wasn’t normal. But all of this was my first time in jail or prison, so I thought that it was the norm: A tenth grader and a seventh grader all in the same class.

I was getting frustrated. I’d think to myself: “How is it that we have a teacher who doesn’t know the answer to certain questions?”

I brought this up with [an advocate]. They were shocked. So, they introduced me to the ACLU-NJ. And from there, the doors opened.

ACLU-NJ: What were the school materials you had like?

Brian Y: We didn’t even have textbooks. They had been recycled for years and were so outdated. The majority of the whole prison was working on the same lessons because it was the only thing they had available.

The teachers are supposed to be there for us, to teach us, but it was a jail mindset, just babysitting — they’d slide worksheets under the door.

ACLU-NJ: When you were in administrative segregation, you received instruction in a literal cage. What was it like to be educated in an environment like that?

Brian Y: I was so young. I don’t even know how to describe it. I felt like an animal.

I’m sitting in a room right now looking at a square table. Now, imagine us in a room. It’s you and the table, and everything around you is three stories high. Everyone is looking down at you.

And you’re in the middle, with lights on you, and a cage all around you. People outside are screaming and yelling. You’re trying to focus — but how can you? You can’t focus.

I remember being in the cage constantly jumping from the sounds. You could put your hand down and unintentionally make a loud noise. You’d hear people folding and stepping on the milk and juice cartons to make popping sounds. You would hear the metal keys. Everything was a loud noise. It was painful. It’s unreal, still thinking about it now. It was sad.

ACLU-NJ: What are your thoughts about missing out on educational services that you should have received?

Brian Y: The seven years I spent in the Department of Corrections, I was cheated out of education, and not learning the things I would have been if I was getting the right education. It’s going to have a huge impact on my life. You know everyone tells you, “Pay attention in school, you’re going to need it.” And here I am now saying the same thing.

ACLU-NJ: You were critical to the development of this case. What was it like to help your lawyers develop the complaint and prepare the suit?

Brian Y: It was exciting being a part of the lawsuit. It was unbelievable. It was like out of a movie. I was like an undercover lawyer. I’d ask questions in the classroom to find out what kinds of services other students were getting — or really, what services they weren’t.

Imagine being locked up at that age and having another inmate coming up to you and asking: “Do you have an IEP? What grade are you in? Why are you doing the same packet I’m doing? Do you get extra tutoring?”

A lot of the work I did to investigate took place when I was put in solitary confinement, taking notes on whatever small pieces of paper I had so I could use them later. Even helping other inmates to fill out forms for legal help: if they couldn’t mail it out themselves, I would put a stamp on it and make sure it got out.

Everyone I talked to or interviewed had a different story, and I was excited to see what impact they could have. It was a challenge for me — to see what I could uncover, or what role the next person I could get involved would have.

ACLU-NJ: After feeling like your concerns were ignored for so long, what was it like after you and your lawyers initiated the suit?

Brian Y: It felt amazing. Like 21 Jump Street, where an investigation blows up, and you laugh about it afterward.

I knew first when the lawsuit was announced and it was covered in the news, because all the teachers started finding out and losing their mind.

Deep down inside, I’m like, “I’m the man, I did this work. I made it happen!” I felt very overwhelmed and joyful.

ACLU-NJ: What did it feel like when you signed the settlement agreement, with your signature on the same document as the Department of Corrections commissioner?

Brian Y: Since getting out, I became a business owner. But signing my name to the changes the Department of Corrections would make felt even more powerful than turning the key to my shop for the first time.

There are so many people inside who have been there for years but didn’t have a way to change anything. Being so young and managing to make the change that we did is amazing.

ACLU-NJ: What differences do you think we’ll see from before the settlement and after?

Brian Y: That’s a good question. And a scary question.

With the settlement and the changes that are coming, there will be new requirements, a monitor to make sure they’re carried out, and all that. It’s scary, because there’s so much that needs to be done. Even when the lawsuit first broke — a lot of people weren’t ready for it.