Thursday, 31 August 2023

Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Technical Assistance Report-Regulation and Supervision of Crypto Assets

Published August 31, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

ACLU: Together, We’re Changing the Face of Crisis Response in D.C.

Ezenwa Oruh was a creative spirit who loved storytelling and was pursuing his dream of being an actor. He was a wonderful uncle to his sister Chioma Oruh’s two children, who are both autistic. Ezenwa also had schizophrenia, and would sometimes become dysregulated and disoriented. Sometimes, his family would have to call 911 for help. They knew the responders would be police, but they had no other option.

“When the police come on site oftentimes — whether it’s for my brother, or the children that I birthed, or other children in the community that go through these crises — the last thing on the mind of a first responder is that these children are brilliant, that they’re loved, that they have gifts, that they offer things to the community,” said Chioma. “The problem is not their family or their condition, but it’s about how the system responds to them and their condition and their loved ones who only seek and want help.”

Chioma and Ezenwa Oruh

Credit : Chioma Oruh

Chioma is one of many Washingtonians for whom the shortcomings of D.C.’s crisis response system, in which police are the default responders for mental and behavioral health crises, hit close to home. Her brother had several emergencies that invariably resulted in police transporting him to the hospital, where he was released shortly after his admission without meaningful treatment and with new traumas of mistreatment by police.

Last year, Ezenwa died. Chioma believes that the repeat encounters with police her brother faced are symptomatic of unequal and unjust social services and medical systems, helmed by an overworked and burnt-out mental health workforce. The presence of police as first responders to mental health crisis calls, she says, are the cumulative result of Ezenwa’s unmet mental health needs. The frequent encounters with police Chioma witnessed and intervened in as a caregiver for her brother were unfortunately a training ground for the frequent police encounters that both her autistic children have endured since they were toddlers.

Following the loss of her brother, Chioma came together with her community to change the city’s crisis response system.

Back in 2019, the ACLU of D.C.’s policy and organizing team formed a small working group to discuss the state of crisis response in the District with local leaders and partners. Community members residing east of the Anacostia River, faith leaders, mutual aid organizers, direct service providers, and public health experts came together to decide if the people of D.C. had the capacity and interest to push for a stronger crisis response system. In 2022, members of this group formed the D.C. Crisis Response Coalition.

The D.C. Crisis Response Coalition’s Theory of Change

The intention of this critical work is to make this a truly community-led effort and bring to the table the expertise of impacted community members first and foremost. Power building is not only essential to the campaign, but is truly the life force of this work.

Through many dialogues over the course of late 2022 and early 2023, the vision for a robust crisis response system in the District became clearer, and we developed our coalition’s platform.

We believe:

- The District’s response to those experiencing mental health crises must center a public health approach with a crisis call center staffed with adequately trained and resourced mental health professionals and services. Police are not equipped or trained for crisis response, nor should they be.

- The District must invest in a crisis response system that is trauma-informed, culturally competent, and inclusive to promote genuine community safety, comprehensive care, and collective well-being. D.C. needs mental health professionals who can respond to emergencies without police and address crises that the call center cannot resolve telephonically.

- Black, Latine, disabled, and senior community members must be connected with the health and wellbeing resources and crisis-receiving centers equipped to address their individual needs during a crisis and connect residents with post-crisis care.

How We Got Here

National experts, federal experts, and the evidence are clear and aligned with the coalition’s position: Police officers aren’t the right people to respond to mental health crises, nor should they be.

Even though the vast majority of people with mental health disabilities are not violent and most people who are violent do not have identifiable mental health disabilities, police nationwide are 11.6 times more likely to use force against people with serious mental health disabilities than other individuals, and 16 times more likely to kill people with untreated mental health disabilities than other individuals. More than half of disabled Black people have been arrested by the time they turn 28 — double the risk of their white disabled peers.

The U.S. Department of Justice has found in multiple investigations that municipalities violate federal disability law by relying on police as the primary first responders for addressing mental health emergencies. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration — the federal agency responsible for mental health — concluded in its national guidelines for behavioral health crisis care that it is “unacceptable and unsafe” for local law enforcement to serve as a community’s de facto mental health crisis first responders.

Credit: TELLYSVISION

Our coalition and allied groups have spoken out against the use of police in crisis response, finding that relying on MPD officers as crisis responders is a fundamental misuse of law enforcement resources and recommending that mental health professionals be the default responders for most mental health emergencies in the District.

Between October 2021 and September 2022, the District dispatched a mental health professional to less than 1 percent of the 911 calls the District received that primarily or exclusively involved mental health emergencies. This was despite the District having mental health clinicians and certified peer support specialists available on its Community Response Teams (CRTs). In contrast, 90 percent of 911 calls related to physical health emergencies during the same year got a response from an EMT or paramedic.

How We’re Taking Action

To support the community’s demands and advocacy, the ACLU and the ACLU of D.C. filed a lawsuit last month challenging the discriminatory crisis response system in Washington D.C. We argue that the disparity between D.C.’s response to physical health emergencies and its response to mental health emergencies is so stark that it violates the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The District has invested the necessary resources to ensure that people experiencing physical health emergencies receive a response from a professional who can assess, stabilize, and if necessary transport the individual to specialized care. But there is no parallel and equivalent system for people who have mental health emergencies.

For example, while the District has hired 1,600 EMTs — 300 of whom are also paramedics (more highly-trained medical professionals) — to respond to physical health emergencies, the District has hired only 44 CRT staff. This understaffing has resulted in response times for CRTs ranging from one to more than three hours, compared to a benchmark of just five minutes for EMT response or nine minutes for paramedic response.

Instead, the District’s policy and practice is to send armed MPD officers to mental health crises, who are not mental health professionals trained to assess, stabilize, and if necessary transport to specialized care. In fact, because many mental health crises are trauma-based, police may make the situation worse. This unequal and discriminatory response violates the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Looking ahead, the coalition will push the D.C. Council and Mayor Bowser to restructure D.C.’s crisis response system. The litigation team will be doing the same in federal court. Together, we hope to achieve a reality in which any District resident can call 911 during a mental health crisis, and Community Response Teams will arrive, equipped with the training and knowledge to help.

Together, we hope to achieve a reality in which any District resident can call 911 during a mental health crisis, and Community Response Teams will arrive, equipped with the training and knowledge to help.

D.C.’s residents are far from alone in this work. There are many other communities actively organizing to make systems of crisis response and care better in their communities. Together, we can move closer to a future where people with mental health disabilities can live freely in our communities alongside their friends and family members, without fear of experiencing harm at the hands of the wrong crisis responder.

Published August 31, 2023 at 11:09PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/nvju1pH

ACLU: Together, We’re Changing the Face of Crisis Response in D.C.

Ezenwa Oruh was a creative spirit who loved storytelling and was pursuing his dream of being an actor. He was a wonderful uncle to his sister Chioma Oruh’s two children, who are both autistic. Ezenwa also had schizophrenia, and would sometimes become dysregulated and disoriented. Sometimes, his family would have to call 911 for help. They knew the responders would be police, but they had no other option.

“When the police come on site oftentimes — whether it’s for my brother, or the children that I birthed, or other children in the community that go through these crises — the last thing on the mind of a first responder is that these children are brilliant, that they’re loved, that they have gifts, that they offer things to the community,” said Chioma. “The problem is not their family or their condition, but it’s about how the system responds to them and their condition and their loved ones who only seek and want help.”

Chioma and Ezenwa Oruh

Credit : Chioma Oruh

Chioma is one of many Washingtonians for whom the shortcomings of D.C.’s crisis response system, in which police are the default responders for mental and behavioral health crises, hit close to home. Her brother had several emergencies that invariably resulted in police transporting him to the hospital, where he was released shortly after his admission without meaningful treatment and with new traumas of mistreatment by police.

Last year, Ezenwa died. Chioma believes that the repeat encounters with police her brother faced are symptomatic of unequal and unjust social services and medical systems, helmed by an overworked and burnt-out mental health workforce. The presence of police as first responders to mental health crisis calls, she says, are the cumulative result of Ezenwa’s unmet mental health needs. The frequent encounters with police Chioma witnessed and intervened in as a caregiver for her brother were unfortunately a training ground for the frequent police encounters that both her autistic children have endured since they were toddlers.

Following the loss of her brother, Chioma came together with her community to change the city’s crisis response system.

Back in 2019, the ACLU of D.C.’s policy and organizing team formed a small working group to discuss the state of crisis response in the District with local leaders and partners. Community members residing east of the Anacostia River, faith leaders, mutual aid organizers, direct service providers, and public health experts came together to decide if the people of D.C. had the capacity and interest to push for a stronger crisis response system. In 2022, members of this group formed the D.C. Crisis Response Coalition.

The D.C. Crisis Response Coalition’s Theory of Change

The intention of this critical work is to make this a truly community-led effort and bring to the table the expertise of impacted community members first and foremost. Power building is not only essential to the campaign, but is truly the life force of this work.

Through many dialogues over the course of late 2022 and early 2023, the vision for a robust crisis response system in the District became clearer, and we developed our coalition’s platform.

We believe:

- The District’s response to those experiencing mental health crises must center a public health approach with a crisis call center staffed with adequately trained and resourced mental health professionals and services. Police are not equipped or trained for crisis response, nor should they be.

- The District must invest in a crisis response system that is trauma-informed, culturally competent, and inclusive to promote genuine community safety, comprehensive care, and collective well-being. D.C. needs mental health professionals who can respond to emergencies without police and address crises that the call center cannot resolve telephonically.

- Black, Latine, disabled, and senior community members must be connected with the health and wellbeing resources and crisis-receiving centers equipped to address their individual needs during a crisis and connect residents with post-crisis care.

How We Got Here

National experts, federal experts, and the evidence are clear and aligned with the coalition’s position: Police officers aren’t the right people to respond to mental health crises, nor should they be.

Even though the vast majority of people with mental health disabilities are not violent and most people who are violent do not have identifiable mental health disabilities, police nationwide are 11.6 times more likely to use force against people with serious mental health disabilities than other individuals, and 16 times more likely to kill people with untreated mental health disabilities than other individuals. More than half of disabled Black people have been arrested by the time they turn 28 — double the risk of their white disabled peers.

The U.S. Department of Justice has found in multiple investigations that municipalities violate federal disability law by relying on police as the primary first responders for addressing mental health emergencies. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration — the federal agency responsible for mental health — concluded in its national guidelines for behavioral health crisis care that it is “unacceptable and unsafe” for local law enforcement to serve as a community’s de facto mental health crisis first responders.

Credit: TELLYSVISION

Our coalition and allied groups have spoken out against the use of police in crisis response, finding that relying on MPD officers as crisis responders is a fundamental misuse of law enforcement resources and recommending that mental health professionals be the default responders for most mental health emergencies in the District.

Between October 2021 and September 2022, the District dispatched a mental health professional to less than 1 percent of the 911 calls the District received that primarily or exclusively involved mental health emergencies. This was despite the District having mental health clinicians and certified peer support specialists available on its Community Response Teams (CRTs). In contrast, 90 percent of 911 calls related to physical health emergencies during the same year got a response from an EMT or paramedic.

How We’re Taking Action

To support the community’s demands and advocacy, the ACLU and the ACLU of D.C. filed a lawsuit last month challenging the discriminatory crisis response system in Washington D.C. We argue that the disparity between D.C.’s response to physical health emergencies and its response to mental health emergencies is so stark that it violates the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The District has invested the necessary resources to ensure that people experiencing physical health emergencies receive a response from a professional who can assess, stabilize, and if necessary transport the individual to specialized care. But there is no parallel and equivalent system for people who have mental health emergencies.

For example, while the District has hired 1,600 EMTs — 300 of whom are also paramedics (more highly-trained medical professionals) — to respond to physical health emergencies, the District has hired only 44 CRT staff. This understaffing has resulted in response times for CRTs ranging from one to more than three hours, compared to a benchmark of just five minutes for EMT response or nine minutes for paramedic response.

Instead, the District’s policy and practice is to send armed MPD officers to mental health crises, who are not mental health professionals trained to assess, stabilize, and if necessary transport to specialized care. In fact, because many mental health crises are trauma-based, police may make the situation worse. This unequal and discriminatory response violates the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Looking ahead, the coalition will push the D.C. Council and Mayor Bowser to restructure D.C.’s crisis response system. The litigation team will be doing the same in federal court. Together, we hope to achieve a reality in which any District resident can call 911 during a mental health crisis, and Community Response Teams will arrive, equipped with the training and knowledge to help.

Together, we hope to achieve a reality in which any District resident can call 911 during a mental health crisis, and Community Response Teams will arrive, equipped with the training and knowledge to help.

D.C.’s residents are far from alone in this work. There are many other communities actively organizing to make systems of crisis response and care better in their communities. Together, we can move closer to a future where people with mental health disabilities can live freely in our communities alongside their friends and family members, without fear of experiencing harm at the hands of the wrong crisis responder.

Published August 31, 2023 at 06:39PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/94Ha6Mb

Botswana: 2023 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Botswana

Published August 31, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Wednesday, 30 August 2023

Haiti: Staff-Monitored Program-Press Release; and Staff Report

Published August 30, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Tuesday, 29 August 2023

Singapore: 2023 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Singapore

Published August 29, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Colombia: Technical Assistance Report—Assessment of Financial Stability Report

Published August 28, 2023 at 08:00PM

Read more at imf.org

ACLU: Meet Mary Wood, a Teacher Resisting Censorship

In the past year, Mary Wood has gone through an ordeal that’s increasingly familiar to teachers, librarians, and school administrators across the country: She is being targeted by activists who want to censor what books are in libraries and what discussions happen in classrooms.

Mary is an English teacher at Chapin High School in Chapin, South Carolina. As originally reported in The State, she assigned Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “Between the World and Me,” a nonfiction book about the Black experience in the United States, as part of a lesson plan on research and argumentation in her advanced placement class. District officials ordered her to stop teaching the book. They alleged that it violated a state budget proviso that forbids a broad range of subject matter involving race and history.

“Between the World and Me” was published in 2015 as an open letter by Coates to his son, reflecting on currents of hope and despair in the struggle for racial justice in the United States. It won the National Book Award for Nonfiction, whose judges said, “Incorporating history and personal memoir, Coates has succeeded in creating an essential text for any thinking American today.”

Coates’ book has been the target of censorship campaigns across the country where book banners are targeting books by and about people of color. In the first half of the 2022-2023 school year, 30 percent of the titles banned were about race, racism, or featured characters of color, according to PEN America. South Carolina is one of five states where book bans have been the most prevalent, alongside Texas, Florida, Missouri, and Utah.

Mary Wood has found herself right in the middle of this nationwide attack on the right to learn and the freedom to read.

The following is an interview with Mary about her experience. It has been edited for length and clarity. For more information about how you can fight back against the wave of school censorship in South Carolina, join the Freedom to Read South Carolina coalition and visit our Students’ Rights page. You can learn more about how the ACLU is defending our right to learn nationwide here.

ACLU: You assigned “Between the World and Me” to an Advanced Placement (AP) Language Arts class. Tell me about that.

Mary Wood: So the lesson plan began with a couple of videos to provide background information about the topic. It discussed racism, redlining, and access to education, which are all topics that Ta-Nehisi Coates covers in his [book]. That was to prepare students. Then I provided a lesson on annotation of texts according to AP standards and expectations, things which should be helpful for them on their essay and in collegiate-level reading and writing. Finally, I provided them with information about different themes that the book touches on, under the umbrella of the Black experience in modern America.

The idea was for them to read the book, identify quotes from the text that covered those different themes, select a theme for themselves, and then research what Coates said about that theme on their own to determine whether or not what he was stating held water — if they agreed with it, if it was valid. The goal was for them to look at a variety of texts from a variety of sources: “Here is an argument. Is it valid?”

We were listening along with Coates’ Audible recitation of the book, and they were to be annotating as they went along. We didn’t get that far — we didn’t get to the part where they do research — because we didn’t finish the book.

ACLU: You and your teaching of this book have been a topic of discussion now at a few school board meetings. At one of the recent meetings, several people noticed that Ta-Nehisi Coates himself showed up and sat with you in the boardroom. Tell me a little bit about how that came about and what it meant to you for him to be there.

Mary Wood: I had given an interview on “The Mehdi Hasan Show,” and Ta-Nehisi’s publicist reached out and asked for my information, and he called. He wanted to talk about what had happened, and he was concerned not for his book specifically, but for censorship in general. He offered that support, and I thought it was a really special and notable thing for him to do.

ACLU: You’ve been personally the subject of all kinds of public comments, from vitriol on the one hand to deep support on the other, and it’s all happened in the town where you grew up. What have you learned about your community while going through this?

Mary Wood: It’s not as staunch as I perhaps thought. I think it’s really easy to assume that the loudest voices are the only voices, but I have seen a different side of that. I saw teachers show up. Teachers in general are afraid to speak out, but the ones who did spoke out in ways that haven’t really happened before. I think that this is important, and it was important to them, so much that they were willing to come out of their comfort zones.

ACLU: How are you feeling about the upcoming school year?

Mary Wood: I’m feeling very anxious, honestly. I don’t know what to expect. The [July 17] board meeting had a wonderful showing of support, not just for me but for educators in general and for the material that we teach. Trusting us is really helpful.

If you look at the board meeting before that, there was a lot of discussion about me deserving to be terminated. One person made a comment that they’ll be keeping their eyes on us. Despite all the kind words and support from the last school board meeting, that one really sticks with you. It stuck with me anyway.

I don’t know what’s going to happen. I don’t know how I’m going to be received by parents and students. I think it’s unfortunate how I’m definitely considering every single thing that I do — and not that I wouldn’t before, but you’re on this heightened alert.

ACLU: This is a challenge that a lot of teachers are facing right now. Is there any advice you’d give to teachers, librarians, anybody who finds themselves in the spotlight like you’ve been?

Mary Wood: I would say it’s important to really look at the policies that are in place. Even though from my perspective I did not break a single policy, I was still said to have. I think it’s really important to not acquiesce just because somebody says something. That doesn’t mean that it’s true.

I would say be bold and don’t back down. Look for resources. Maybe I’m fortunate enough that this story did make national headlines so that it drew attention from the likes of Ta-Nehisi Coates, from the National Education Association, from other people who are really valuable resources. If I could do anything, it would be to find a way to bring this all together.

This blog was originally published by the ACLU of South Carolina.

Published August 29, 2023 at 08:21PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/kZMwvQs

ACLU: Meet Mary Wood, a Teacher Resisting Censorship

In the past year, Mary Wood has gone through an ordeal that’s increasingly familiar to teachers, librarians, and school administrators across the country: She is being targeted by activists who want to censor what books are in libraries and what discussions happen in classrooms.

Mary is an English teacher at Chapin High School in Chapin, South Carolina. As originally reported in The State, she assigned Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “Between the World and Me,” a nonfiction book about the Black experience in the United States, as part of a lesson plan on research and argumentation in her advanced placement class. District officials ordered her to stop teaching the book. They alleged that it violated a state budget proviso that forbids a broad range of subject matter involving race and history.

“Between the World and Me” was published in 2015 as an open letter by Coates to his son, reflecting on currents of hope and despair in the struggle for racial justice in the United States. It won the National Book Award for Nonfiction, whose judges said, “Incorporating history and personal memoir, Coates has succeeded in creating an essential text for any thinking American today.”

Coates’ book has been the target of censorship campaigns across the country where book banners are targeting books by and about people of color. In the first half of the 2022-2023 school year, 30 percent of the titles banned were about race, racism, or featured characters of color, according to PEN America. South Carolina is one of five states where book bans have been the most prevalent, alongside Texas, Florida, Missouri, and Utah.

Mary Wood has found herself right in the middle of this nationwide attack on the right to learn and the freedom to read.

The following is an interview with Mary about her experience. It has been edited for length and clarity. For more information about how you can fight back against the wave of school censorship in South Carolina, join the Freedom to Read South Carolina coalition and visit our Students’ Rights page. You can learn more about how the ACLU is defending our right to learn nationwide here.

ACLU: You assigned “Between the World and Me” to an Advanced Placement (AP) Language Arts class. Tell me about that.

Mary Wood: So the lesson plan began with a couple of videos to provide background information about the topic. It discussed racism, redlining, and access to education, which are all topics that Ta-Nehisi Coates covers in his [book]. That was to prepare students. Then I provided a lesson on annotation of texts according to AP standards and expectations, things which should be helpful for them on their essay and in collegiate-level reading and writing. Finally, I provided them with information about different themes that the book touches on, under the umbrella of the Black experience in modern America.

The idea was for them to read the book, identify quotes from the text that covered those different themes, select a theme for themselves, and then research what Coates said about that theme on their own to determine whether or not what he was stating held water — if they agreed with it, if it was valid. The goal was for them to look at a variety of texts from a variety of sources: “Here is an argument. Is it valid?”

We were listening along with Coates’ Audible recitation of the book, and they were to be annotating as they went along. We didn’t get that far — we didn’t get to the part where they do research — because we didn’t finish the book.

ACLU: You and your teaching of this book have been a topic of discussion now at a few school board meetings. At one of the recent meetings, several people noticed that Ta-Nehisi Coates himself showed up and sat with you in the boardroom. Tell me a little bit about how that came about and what it meant to you for him to be there.

Mary Wood: I had given an interview on “The Mehdi Hasan Show,” and Ta-Nehisi’s publicist reached out and asked for my information, and he called. He wanted to talk about what had happened, and he was concerned not for his book specifically, but for censorship in general. He offered that support, and I thought it was a really special and notable thing for him to do.

ACLU: You’ve been personally the subject of all kinds of public comments, from vitriol on the one hand to deep support on the other, and it’s all happened in the town where you grew up. What have you learned about your community while going through this?

Mary Wood: It’s not as staunch as I perhaps thought. I think it’s really easy to assume that the loudest voices are the only voices, but I have seen a different side of that. I saw teachers show up. Teachers in general are afraid to speak out, but the ones who did spoke out in ways that haven’t really happened before. I think that this is important, and it was important to them, so much that they were willing to come out of their comfort zones.

ACLU: How are you feeling about the upcoming school year?

Mary Wood: I’m feeling very anxious, honestly. I don’t know what to expect. The [July 17] board meeting had a wonderful showing of support, not just for me but for educators in general and for the material that we teach. Trusting us is really helpful.

If you look at the board meeting before that, there was a lot of discussion about me deserving to be terminated. One person made a comment that they’ll be keeping their eyes on us. Despite all the kind words and support from the last school board meeting, that one really sticks with you. It stuck with me anyway.

I don’t know what’s going to happen. I don’t know how I’m going to be received by parents and students. I think it’s unfortunate how I’m definitely considering every single thing that I do — and not that I wouldn’t before, but you’re on this heightened alert.

ACLU: This is a challenge that a lot of teachers are facing right now. Is there any advice you’d give to teachers, librarians, anybody who finds themselves in the spotlight like you’ve been?

Mary Wood: I would say it’s important to really look at the policies that are in place. Even though from my perspective I did not break a single policy, I was still said to have. I think it’s really important to not acquiesce just because somebody says something. That doesn’t mean that it’s true.

I would say be bold and don’t back down. Look for resources. Maybe I’m fortunate enough that this story did make national headlines so that it drew attention from the likes of Ta-Nehisi Coates, from the National Education Association, from other people who are really valuable resources. If I could do anything, it would be to find a way to bring this all together.

This blog was originally published by the ACLU of South Carolina.

Published August 29, 2023 at 03:51PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/YJFxT1V

Monday, 28 August 2023

New Zealand: 2023 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for New Zealand

Published August 28, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Friday, 25 August 2023

Argentina: Fifth and Sixth Reviews Under the Extended Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility, Request for Rephasing of Access, Waivers of Nonobservance of Performance Criteria, Modification of Performance Criteria and Financing Assurances Review-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Argentina

Published August 25, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Chile: Review Under the Flexible Credit Line Arrangement-Press Release; Staff Report; Staff Supplement; and Statement by the Executive Director for Chile

Published August 25, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Wednesday, 23 August 2023

ACLU: How Artificial Intelligence Might Prevent You From Getting Hired

If you applied for a new job in the last few years, chances are an artificial intelligence (AI) tool was used to make decisions impacting whether or not you got the job. Long before ChatGPT and generative AI ushered in a flood of public discussion about the dangers of AI, private companies and government agencies had already incorporated AI tools into just about every facet of our daily lives, including in housing, education, finance, public benefits, law enforcement, and health care. Recent reports indicate that 70 percent of companies and 99 percent of Fortune 500 companies are already using AI-based and other automated tools in their hiring processes, with increasing use in lower wage job sectors such as retail and food services where Black and Latine workers are disproportionately concentrated.

AI-based tools have been incorporated into virtually every stage of the hiring process. They are used to target online advertising for job opportunities and to match candidates to jobs and vice versa on platforms such as LinkedIn and ZipRecruiter. They are used to reject or rank applicants using automated resume screening and chatbots based on knockout questions, keyword requirements, or specific qualifications or characteristics. They are used to assess and measure often amorphous personality characteristics, sometimes through online versions of multiple-choice tests that ask situational or outlook questions, and sometimes through video-game style tools that analyze how someone plays a game. And if you have ever been asked to record a video of yourself as part of an application, a human may or may not have ever viewed it: Some employers instead use AI tools that purport to measure personality traits through voice analysis of tone, pitch, and word choice and video analysis of facial movements and expressions.

Many of these tools pose an enormous danger of exacerbating existing discrimination in the workplace based on race, sex, disability, and other protected characteristics, despite marketing claims that they are objective and less discriminatory. AI tools are trained with a large amount of data and make predictions about future outcomes based on correlations and patterns in that data — many tools that employers are using are trained on data about the employer’s own workforce and prior hiring processes. But that data is itself reflective of existing institutional and systemic biases.

Moreover, the correlations that an AI tool uncovers may not actually have a causal connection with being a successful employee, may not themselves be job-related, and may be proxies for protected characteristics. For example, one resume screening tool identified being named Jared and playing high school lacrosse as correlated with being a successful employee. Likewise, the amorphous personality traits that many AI tools are designed to measure — characteristics such as positivity, ability to handle pressure, or extroversion — are often not necessary for the job, may reflect standards and norms that are culturally specific, or can screen out candidates with disabilities such as autism, depression, or attention deficit disorder.

Predictive tools that rely on analysis of facial, audio, or physical interaction with a computer are even worse. We are extremely skeptical that it’s possible to measure personality characteristics accurately through things such as how fast someone clicks a mouse, the tone of a person’s voice, or facial expressions. And even if it is possible, predictive tools that rely on analysis of facial, audio, or physical interaction with a computer increase the risk that individuals will be automatically rejected or scored lower on the basis of disabilities, race, and other protected characteristics.

Beyond questions of efficacy and fairness, people often have little or no awareness that such tools are being used, let alone how they work or that these tools may be making discriminatory decisions about them. Applicants often do not have enough information about the process to know whether to seek an accommodation on the basis of disability, and the lack of transparency makes it more difficult to detect discrimination and for individuals, private lawyers, and government agencies to enforce civil rights laws.

How Can We Prevent the Use of Discriminatory AI Tools in Hiring?

Employers must stop using automated tools that carry a high risk of screening people out based on disabilities, race, sex, and other protected characteristics. It is critical that any tools employers do consider adopting undergo robust third party assessments for discrimination, and that employers provide applicants with proper notice and accommodations.

We also need strong regulation and enforcement of existing protections against employment discrimination. Civil rights laws bar discrimination in hiring whether it’s happening through online processes or otherwise, so regulators already have the authority and obligation to protect people in the labor market from the harms of AI tools, and individuals can assert their rights in court. Agencies such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission have taken some initial steps to inform employers about their obligations, but they should follow that up by creating standards for impact assessments, notice, and recourse, and engage in enforcement actions when employers fail to comply.

Legislators also have a role to play. State legislatures and Congress have begun considering legislation to help job applicants and employees ensure that the uses of AI tools in employment are fair and nondiscriminatory. These legislative efforts are diverse, and may be roughly divided into three categories.

First, some efforts focus on providing transparency around the use of AI, especially to make decisions in protected areas of life, including employment. These bills require employers to provide individuals not only with notice that AI was or will be used to make a decision about their hiring or employment, but also with the data (or a description of the data) used to make that decision and how the AI system reaches its ultimate decision.

Second, other legislation requires that entities deploying AI tools assess their impact on privacy and nondiscrimination. This kind of legislation may require impact assessments for AI hiring tools to better understand their potential negative effects and to identify strategies to mitigate those effects. Although these bills may not create an enforcement mechanism, they are critical to forcing companies to take protective measures before deploying AI tools.

Third, some legislatures are considering bills that would impose additional non-discrimination responsibilities on employers using AI tools and would plug some gaps in existing civil rights protections. For example, last year’s American Data Privacy and Protection Act included language that prohibited using data — including in AI tools — “in a manner that discriminates in or otherwise makes unavailable the equal enjoyment of goods or services on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, or disability.” Some state legislation would ban uses of particularly high-risk AI tools.

These approaches across agencies and legislatures complement one another as we take steps to protect job applicants and employees in a quickly evolving space. AI tools have an increasingly important and prevalent role in our everyday lives, and policymakers must respond to that immediate threat.

Published August 24, 2023 at 03:02AM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/fL65ZeK

ACLU: How Artificial Intelligence Might Prevent You From Getting Hired

If you applied for a new job in the last few years, chances are an artificial intelligence (AI) tool was used to make decisions impacting whether or not you got the job. Long before ChatGPT and generative AI ushered in a flood of public discussion about the dangers of AI, private companies and government agencies had already incorporated AI tools into just about every facet of our daily lives, including in housing, education, finance, public benefits, law enforcement, and health care. Recent reports indicate that 70 percent of companies and 99 percent of Fortune 500 companies are already using AI-based and other automated tools in their hiring processes, with increasing use in lower wage job sectors such as retail and food services where Black and Latine workers are disproportionately concentrated.

AI-based tools have been incorporated into virtually every stage of the hiring process. They are used to target online advertising for job opportunities and to match candidates to jobs and vice versa on platforms such as LinkedIn and ZipRecruiter. They are used to reject or rank applicants using automated resume screening and chatbots based on knockout questions, keyword requirements, or specific qualifications or characteristics. They are used to assess and measure often amorphous personality characteristics, sometimes through online versions of multiple-choice tests that ask situational or outlook questions, and sometimes through video-game style tools that analyze how someone plays a game. And if you have ever been asked to record a video of yourself as part of an application, a human may or may not have ever viewed it: Some employers instead use AI tools that purport to measure personality traits through voice analysis of tone, pitch, and word choice and video analysis of facial movements and expressions.

Many of these tools pose an enormous danger of exacerbating existing discrimination in the workplace based on race, sex, disability, and other protected characteristics, despite marketing claims that they are objective and less discriminatory. AI tools are trained with a large amount of data and make predictions about future outcomes based on correlations and patterns in that data — many tools that employers are using are trained on data about the employer’s own workforce and prior hiring processes. But that data is itself reflective of existing institutional and systemic biases.

Moreover, the correlations that an AI tool uncovers may not actually have a causal connection with being a successful employee, may not themselves be job-related, and may be proxies for protected characteristics. For example, one resume screening tool identified being named Jared and playing high school lacrosse as correlated with being a successful employee. Likewise, the amorphous personality traits that many AI tools are designed to measure — characteristics such as positivity, ability to handle pressure, or extroversion — are often not necessary for the job, may reflect standards and norms that are culturally specific, or can screen out candidates with disabilities such as autism, depression, or attention deficit disorder.

Predictive tools that rely on analysis of facial, audio, or physical interaction with a computer are even worse. We are extremely skeptical that it’s possible to measure personality characteristics accurately through things such as how fast someone clicks a mouse, the tone of a person’s voice, or facial expressions. And even if it is possible, predictive tools that rely on analysis of facial, audio, or physical interaction with a computer increase the risk that individuals will be automatically rejected or scored lower on the basis of disabilities, race, and other protected characteristics.

Beyond questions of efficacy and fairness, people often have little or no awareness that such tools are being used, let alone how they work or that these tools may be making discriminatory decisions about them. Applicants often do not have enough information about the process to know whether to seek an accommodation on the basis of disability, and the lack of transparency makes it more difficult to detect discrimination and for individuals, private lawyers, and government agencies to enforce civil rights laws.

How Can We Prevent the Use of Discriminatory AI Tools in Hiring?

Employers must stop using automated tools that carry a high risk of screening people out based on disabilities, race, sex, and other protected characteristics. It is critical that any tools employers do consider adopting undergo robust third party assessments for discrimination, and that employers provide applicants with proper notice and accommodations.

We also need strong regulation and enforcement of existing protections against employment discrimination. Civil rights laws bar discrimination in hiring whether it’s happening through online processes or otherwise, so regulators already have the authority and obligation to protect people in the labor market from the harms of AI tools, and individuals can assert their rights in court. Agencies such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission have taken some initial steps to inform employers about their obligations, but they should follow that up by creating standards for impact assessments, notice, and recourse, and engage in enforcement actions when employers fail to comply.

Legislators also have a role to play. State legislatures and Congress have begun considering legislation to help job applicants and employees ensure that the uses of AI tools in employment are fair and nondiscriminatory. These legislative efforts are diverse, and may be roughly divided into three categories.

First, some efforts focus on providing transparency around the use of AI, especially to make decisions in protected areas of life, including employment. These bills require employers to provide individuals not only with notice that AI was or will be used to make a decision about their hiring or employment, but also with the data (or a description of the data) used to make that decision and how the AI system reaches its ultimate decision.

Second, other legislation requires that entities deploying AI tools assess their impact on privacy and nondiscrimination. This kind of legislation may require impact assessments for AI hiring tools to better understand their potential negative effects and to identify strategies to mitigate those effects. Although these bills may not create an enforcement mechanism, they are critical to forcing companies to take protective measures before deploying AI tools.

Third, some legislatures are considering bills that would impose additional non-discrimination responsibilities on employers using AI tools and would plug some gaps in existing civil rights protections. For example, last year’s American Data Privacy and Protection Act included language that prohibited using data — including in AI tools — “in a manner that discriminates in or otherwise makes unavailable the equal enjoyment of goods or services on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, or disability.” Some state legislation would ban uses of particularly high-risk AI tools.

These approaches across agencies and legislatures complement one another as we take steps to protect job applicants and employees in a quickly evolving space. AI tools have an increasingly important and prevalent role in our everyday lives, and policymakers must respond to that immediate threat.

Published August 23, 2023 at 10:32PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/UF76dcv

Côte d'Ivoire: Report on Observance of Standards and Codes—FATF Recommendations for Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism

Published August 23, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Monday, 21 August 2023

The Bahamas: Technical Assistance Report-Operationalizing the New Bank Resolution Framework and Amended Deposit Insurance Legislation—First Mission

Published August 21, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Monday, 14 August 2023

ACLU: Hotel Accessibility Reaches the Supreme Court

As a wheelchair user with multiple disabilities, travel is unpredictable at best and completely inaccessible at worst. In order to book my trips, I have to trust the accuracy of the websites run by hotels, airlines, car rental companies, and more to learn whether I can use their services (i.e., have the honor of paying them my hard-earned money.) The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires hotels to include enough of their accessibility features on their website that a person with a disability can judge whether their hotel would be safe and usable. Unfortunately, the features they include are often incomplete or inaccurate.

Travel may be a luxury, but accessibility is a necessity and a right.

Hotels rarely identify what types of accommodations are available in their “accessible” rooms. At times, I will arrive to find my room is accessible for someone with an auditory disability, but not for a mobility disability like mine. While not necessary for me, having a visual or tactile fire alarm in their room could be the difference between life and death in an emergency for someone with an auditory disability. Hotels often take a kitchen sink approach to accessibility, throwing in a visual accommodation here and a mobility accommodation there, but failing to provide full accessibility to either group. This overlooks the point of accessibility, effectively making the room useless to many disabled travelers.

This “too little, too late” approach applies across the board with hotel accommodations. On three of my recent trips, I found that the shower in my room did not have a bench to transfer onto. Hotels ought to have shower chairs available in these scenarios; frequently, they do not, leaving me no choice but to lay or sit on the floor of a shower to clean myself. My friend Michelle, who uses a wheelchair, can’t shower at all in these situations. On three of five recent trips, Michelle has found herself assigned to an inaccessible room despite booking an accessible one. Even in “accessible” rooms, beds may be too high for people to transfer out of their wheelchairs safely, leaving some travelers to sleep in their wheelchairs.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires hotels to include enough of their accessibility features on their website that a person with a disability can judge whether their hotel would be safe and usable.

My friend Alex, who also uses a wheelchair, shared that she must rely on her husband every time she travels to fill in gaps in hotel accessibility, from assistance transferring to navigating the room itself. Furniture regularly crowds hotel rooms in a way that leaves little room to maneuver a wheelchair, scooter, or walker. When we have to ask the hotel to remove some of this furniture, it can result in the removal of the very amenities we paid for — a desk to work remotely, for example. Unreliable accessibility makes it challenging or impossible for people with disabilities to travel independently; we simply do not know what lies on the other side of the door, forcing us to plan ahead and rely on others in anticipation of barriers.

The law only requires hotels to make a small percentage of their rooms accessible, compounding the problems disabled travelers face. Twice in the last year, I have arrived at a hotel only to be told that, despite having paid for early check-in, I would have to wait several hours in the lobby for the room’s current resident to depart. When pressed, it became apparent that it was the only accessible room available in the hotel, leaving me no choice but to wait. This problem often occurs because hotels will assign non-disabled patrons to their very limited number of accessible rooms to maximize profits — at the expense of disabled patrons’ access.

The upcoming Supreme Court case Acheson Hotels v. Laufer illustrates how hotels often fail travelers with disabilities, and offers an opportunity to solidify our right to hold hotels and other public accommodations accountable for these failures.

The upcoming Supreme Court case Acheson Hotels v. Laufer illustrates how hotels often fail travelers with disabilities, and offers an opportunity to solidify our right to hold hotels and other public accommodations accountable for these failures. Deborah Laufer, a person with disabilities, sued Acheson Hotels, LLC for failing to make clear whether the hotel was accessible on their website as required by the ADA. Now, the issue before the Supreme Court is whether Laufer can sue Acheson even though she has not visited their hotels and is not likely to. She is what many call a civil rights “tester.” Being a tester in civil rights cases is an honored and necessary role. It has evolved over the years, from Black patrons trying to enter a “whites only” waiting room, to women applying for typically male jobs, to families applying to “singles only” housing. In each case, the “tester” has no intention of taking the job or renting the housing — but, as a member of the class of people facing discrimination, can go to court to enforce civil rights laws.

As we outlined in a friend-of-the-court brief filed last week in the case, as a person with disabilities, Laufer is harmed, like any traveler with a disability, by Acheson’s failure to provide equal access to its accommodations. Laufer has every right to assert disabled people’s right to access knowledge of accessibility features; without it, how can we make informed decisions about where we will stay? How do we know the rooms will preserve our dignity by not leaving us to sit on the floor of showers or sleep in our wheelchairs? Allowing “testers” like Laufer to bring suit is a necessary component of enforcing disability law and promoting broad compliance with the ADA.

Travel may be a luxury, but accessibility is a necessity and a right. Until we make accessibility features widely and consistently available, travelers with disabilities will continue to face barriers and indignities where our non-disabled peers do not.

Published August 15, 2023 at 01:04AM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/f9Mvsar

ACLU: Hotel Accessibility Reaches the Supreme Court

As a wheelchair user with multiple disabilities, travel is unpredictable at best and completely inaccessible at worst. In order to book my trips, I have to trust the accuracy of the websites run by hotels, airlines, car rental companies, and more to learn whether I can use their services (i.e., have the honor of paying them my hard-earned money.) The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires hotels to include enough of their accessibility features on their website that a person with a disability can judge whether their hotel would be safe and usable. Unfortunately, the features they include are often incomplete or inaccurate.

Travel may be a luxury, but accessibility is a necessity and a right.

Hotels rarely identify what types of accommodations are available in their “accessible” rooms. At times, I will arrive to find my room is accessible for someone with an auditory disability, but not for a mobility disability like mine. While not necessary for me, having a visual or tactile fire alarm in their room could be the difference between life and death in an emergency for someone with an auditory disability. Hotels often take a kitchen sink approach to accessibility, throwing in a visual accommodation here and a mobility accommodation there, but failing to provide full accessibility to either group. This overlooks the point of accessibility, effectively making the room useless to many disabled travelers.

This “too little, too late” approach applies across the board with hotel accommodations. On three of my recent trips, I found that the shower in my room did not have a bench to transfer onto. Hotels ought to have shower chairs available in these scenarios; frequently, they do not, leaving me no choice but to lay or sit on the floor of a shower to clean myself. My friend Michelle, who uses a wheelchair, can’t shower at all in these situations. On three of five recent trips, Michelle has found herself assigned to an inaccessible room despite booking an accessible one. Even in “accessible” rooms, beds may be too high for people to transfer out of their wheelchairs safely, leaving some travelers to sleep in their wheelchairs.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires hotels to include enough of their accessibility features on their website that a person with a disability can judge whether their hotel would be safe and usable.

My friend Alex, who also uses a wheelchair, shared that she must rely on her husband every time she travels to fill in gaps in hotel accessibility, from assistance transferring to navigating the room itself. Furniture regularly crowds hotel rooms in a way that leaves little room to maneuver a wheelchair, scooter, or walker. When we have to ask the hotel to remove some of this furniture, it can result in the removal of the very amenities we paid for — a desk to work remotely, for example. Unreliable accessibility makes it challenging or impossible for people with disabilities to travel independently; we simply do not know what lies on the other side of the door, forcing us to plan ahead and rely on others in anticipation of barriers.

The law only requires hotels to make a small percentage of their rooms accessible, compounding the problems disabled travelers face. Twice in the last year, I have arrived at a hotel only to be told that, despite having paid for early check-in, I would have to wait several hours in the lobby for the room’s current resident to depart. When pressed, it became apparent that it was the only accessible room available in the hotel, leaving me no choice but to wait. This problem often occurs because hotels will assign non-disabled patrons to their very limited number of accessible rooms to maximize profits — at the expense of disabled patrons’ access.

The upcoming Supreme Court case Acheson Hotels v. Laufer illustrates how hotels often fail travelers with disabilities, and offers an opportunity to solidify our right to hold hotels and other public accommodations accountable for these failures.

The upcoming Supreme Court case Acheson Hotels v. Laufer illustrates how hotels often fail travelers with disabilities, and offers an opportunity to solidify our right to hold hotels and other public accommodations accountable for these failures. Deborah Laufer, a person with disabilities, sued Acheson Hotels, LLC for failing to make clear whether the hotel was accessible on their website as required by the ADA. Now, the issue before the Supreme Court is whether Laufer can sue Acheson even though she has not visited their hotels and is not likely to. She is what many call a civil rights “tester.” Being a tester in civil rights cases is an honored and necessary role. It has evolved over the years, from Black patrons trying to enter a “whites only” waiting room, to women applying for typically male jobs, to families applying to “singles only” housing. In each case, the “tester” has no intention of taking the job or renting the housing — but, as a member of the class of people facing discrimination, can go to court to enforce civil rights laws.

As we outlined in a friend-of-the-court brief filed last week in the case, as a person with disabilities, Laufer is harmed, like any traveler with a disability, by Acheson’s failure to provide equal access to its accommodations. Laufer has every right to assert disabled people’s right to access knowledge of accessibility features; without it, how can we make informed decisions about where we will stay? How do we know the rooms will preserve our dignity by not leaving us to sit on the floor of showers or sleep in our wheelchairs? Allowing “testers” like Laufer to bring suit is a necessary component of enforcing disability law and promoting broad compliance with the ADA.

Travel may be a luxury, but accessibility is a necessity and a right. Until we make accessibility features widely and consistently available, travelers with disabilities will continue to face barriers and indignities where our non-disabled peers do not.

Published August 14, 2023 at 08:34PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/snHzceO

ACLU: Don't Let the Math Distract You: Together, We Can Fight Algorithmic Injustice

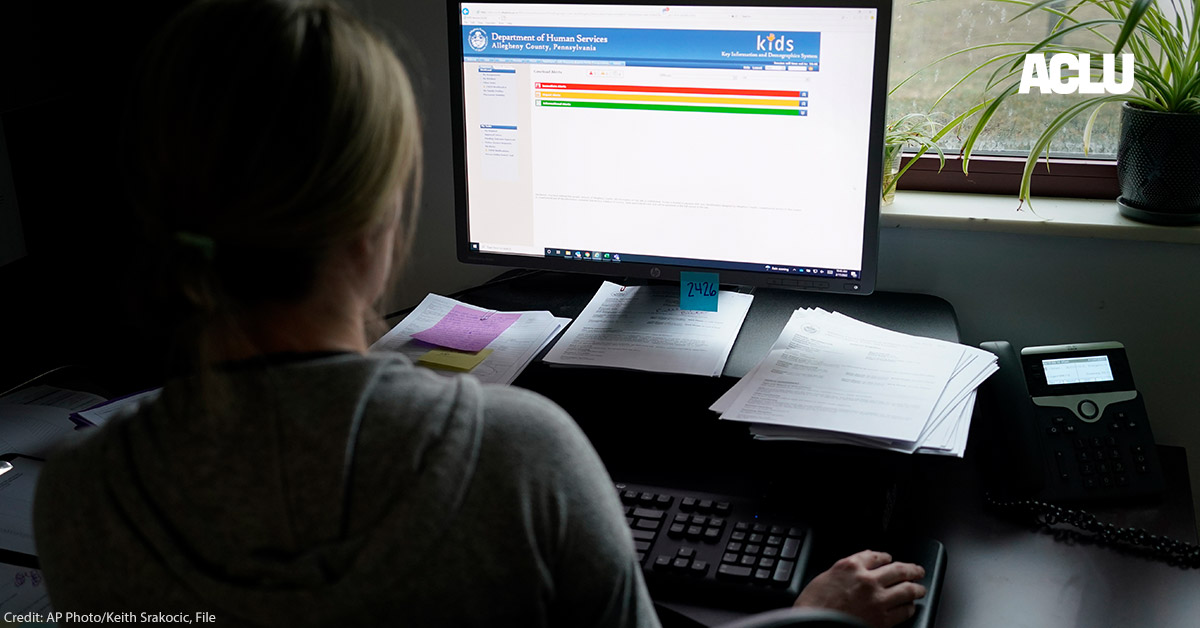

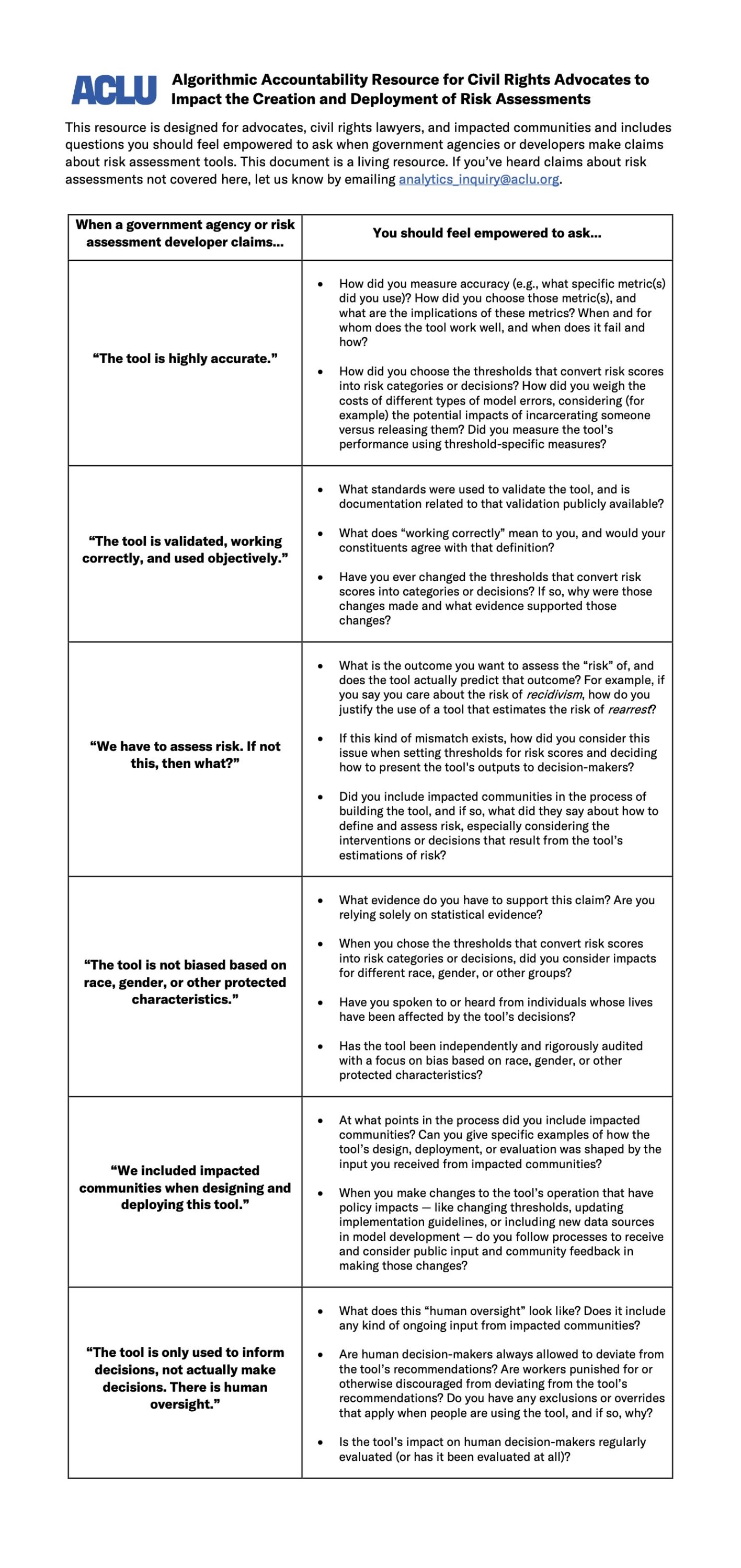

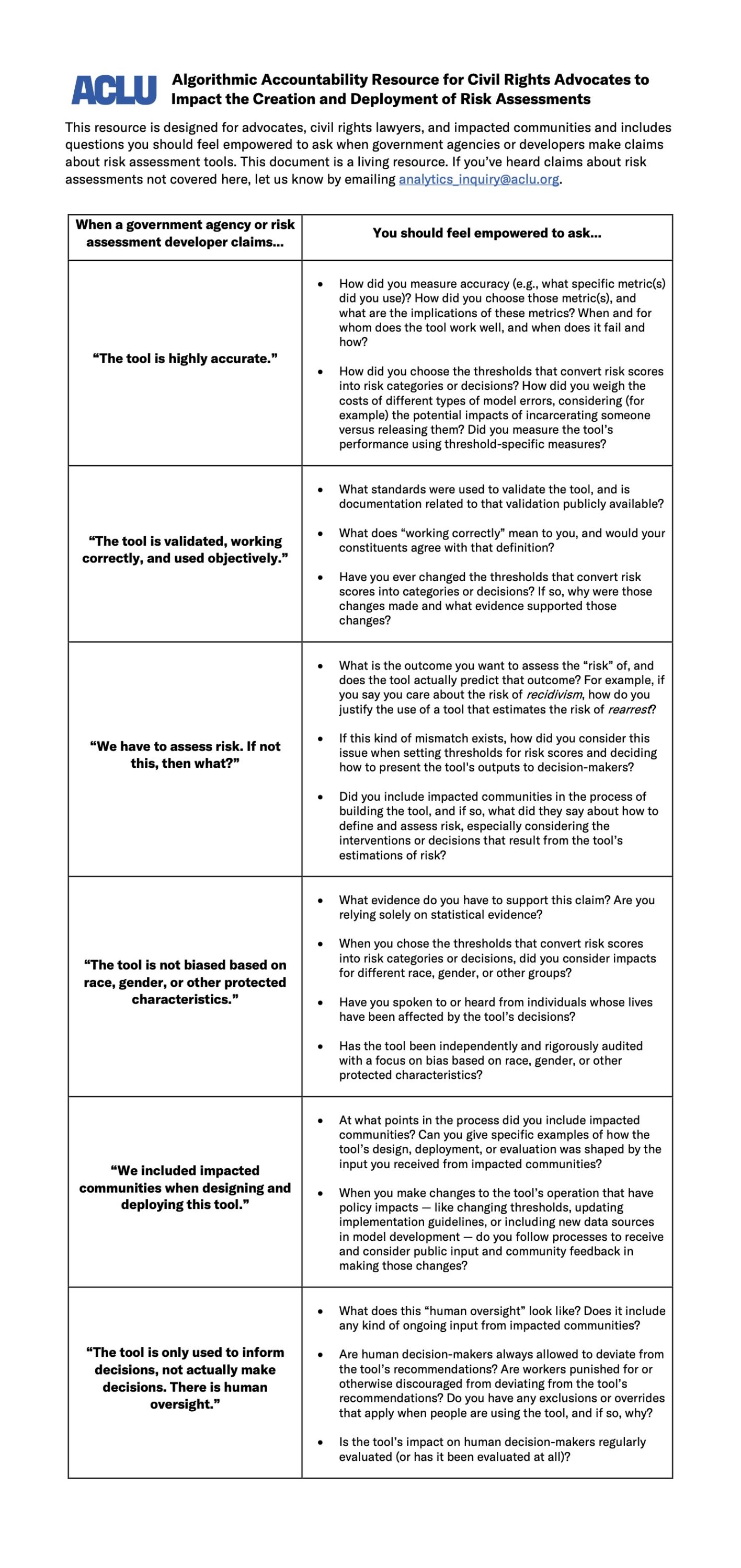

Around the country, automated systems are being used to inform crucial decisions about people’s lives. These systems, often referred to as “risk assessment tools,” are used to decide whether defendants will be released pretrial, whether to investigate allegations of child neglect, to predict which students might drop out of high school, and more.

The developers of these tools and government agencies that use them often claim that risk assessments will improve human decisions by using data. But risk assessment tools (and the data used to build them) are not just technical systems that exist in isolation — they are inherently intertwined with the policies and politics of the systems in which they operate, and they can reproduce the biases of those systems.

How do these kinds of algorithmic risk assessment tools affect people’s lives?

The Department of Justice used one of these tools, PATTERN, to inform decisions about whether incarcerated people would be released from prison to home confinement at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. PATTERN outputs “risk scores” — essentially numbers that estimate how likely it is a person will be rearrested or returned to custody after their release. Thresholds are then used to convert these scores into risk categories, so for example, a score below a certain number may be considered “low risk,” while scores at or above that number may be classified as “high risk,” and so on.

While PATTERN was not designed to assess risks related to a public health emergency (and hundreds of civil rights organizations opposed its use in this manner), the DOJ decided that only people whose risk scores were considered “minimum” should be prioritized for consideration for home confinement. But deciding who should be released from prison in the midst of a public health emergency is not just a question of mathematics. It is also fundamentally a question of policy.

How are risk assessment tools and policy decisions intertwined?

In a new research paper, we demonstrate that developers repeatedly bake policy decisions into the design of risk assessments under the guise of mathematical formalisms. We argue that this dynamic is a “framing trap” — where choices that should be made by policymakers, advocates, and those directly impacted by a risk assessment’s use are improperly hidden behind a veil of mathematical rigor.

In the case of PATTERN, a key metric, “Area Under the Curve” (AUC), is used to support claims about the tool’s predictive accuracy and to make arguments about the tool’s “racial neutrality.” Our research shows that AUC is often used in ways that are mathematically unsound or that hide or defer these questions of policy. In this example, AUC measures the probability that a formerly incarcerated person who was re-arrested or returned to custody was given a higher risk score by PATTERN than someone who did not return to prison. While AUC can tell us if a higher risk score is correlated with a higher chance of re-arrest, we argue that it is problematic to make broad claims about whether a tool is racially biased solely based on AUC values.

This metric also ignores the existence of the thresholds that create groupings like “high risk” and “low risk.” These groupings are crucial, and they are not neutral. When the DOJ used PATTERN to inform release decisions at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, they reportedly secretly altered the threshold that determines whether someone is classified as “minimum risk,” meaning far fewer people would qualify to be considered for release.

We argue that any choice about who gets classified into each of these groups represents an implicit policy judgement about the value of freedom and harms of incarceration. Though this change may have been framed as a decision based on data and mathematics, the DOJ essentially made a policy choice about the societal costs of releasing people to their homes and families relative to the costs of incarceration, arguably manipulating thresholds to effect policy decisions.

So, why should civil rights advocates care about this?

In our work assessing the impacts of automated systems, we see this dynamic repeatedly: government agencies rely on sloppy use of scientific concepts, such as using AUC as a seal of approval to justify the use of a model. Agencies or tool developers then set thresholds that determine whether people are kept in prison during a pandemic, whether they are jailed prior to trial, or whether their homes are entered without warrants.

Yet this threshold-setting and manipulation often happens behind closed doors. Mathematical rigor is often prioritized over the input of civil rights advocates and impacted communities, and civil rights advocates and impacted communities are routinely excluded from crucial conversations about how these tools are designed or whether they should be designed at all. Ultimately, this veiling of policy with mathematics has grave consequences for our ability to demand accountability from those who seek to deploy risk assessments.

How can we ensure that government agencies and other decision-makers are held accountable for the potential harm that risk assessment tools may cause?

We must insist that tool designers and governments lift the veil on the critical policy decisions embedded in these tools — from the data sets used to develop these tools, to what risks the tools assess, to how the tools ultimately box people into risk categories. This is especially true for criminal and civil defense attorneys whose clients face life-altering consequences from being labeled “too risky.” Data scientists and other experts must help communities cut through the technical language of tool designers to lay bare their policy implications. Better yet, advocates and impacted communities must insist on a seat at the table to make threshold and other decisions that represent implicit or explicit policymaking in the creation of risk assessments.

To push for this change, we’ve created a resource for advocates, lawyers, and impacted communities, including questions you should feel empowered to ask when government agencies or developers make claims about risk assessment tools:

Published August 8, 2023 at 09:08PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/h39WjcF

ACLU: Don't Let the Math Distract You: Together, We Can Fight Algorithmic Injustice

Around the country, automated systems are being used to inform crucial decisions about people’s lives. These systems, often referred to as “risk assessment tools,” are used to decide whether defendants will be released pretrial, whether to investigate allegations of child neglect, to predict which students might drop out of high school, and more.

The developers of these tools and government agencies that use them often claim that risk assessments will improve human decisions by using data. But risk assessment tools (and the data used to build them) are not just technical systems that exist in isolation — they are inherently intertwined with the policies and politics of the systems in which they operate, and they can reproduce the biases of those systems.

How do these kinds of algorithmic risk assessment tools affect people’s lives?

The Department of Justice used one of these tools, PATTERN, to inform decisions about whether incarcerated people would be released from prison to home confinement at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. PATTERN outputs “risk scores” — essentially numbers that estimate how likely it is a person will be rearrested or returned to custody after their release. Thresholds are then used to convert these scores into risk categories, so for example, a score below a certain number may be considered “low risk,” while scores at or above that number may be classified as “high risk,” and so on.

While PATTERN was not designed to assess risks related to a public health emergency (and hundreds of civil rights organizations opposed its use in this manner), the DOJ decided that only people whose risk scores were considered “minimum” should be prioritized for consideration for home confinement. But deciding who should be released from prison in the midst of a public health emergency is not just a question of mathematics. It is also fundamentally a question of policy.

How are risk assessment tools and policy decisions intertwined?

In a new research paper, we demonstrate that developers repeatedly bake policy decisions into the design of risk assessments under the guise of mathematical formalisms. We argue that this dynamic is a “framing trap” — where choices that should be made by policymakers, advocates, and those directly impacted by a risk assessment’s use are improperly hidden behind a veil of mathematical rigor.

In the case of PATTERN, a key metric, “Area Under the Curve” (AUC), is used to support claims about the tool’s predictive accuracy and to make arguments about the tool’s “racial neutrality.” Our research shows that AUC is often used in ways that are mathematically unsound or that hide or defer these questions of policy. In this example, AUC measures the probability that a formerly incarcerated person who was re-arrested or returned to custody was given a higher risk score by PATTERN than someone who did not return to prison. While AUC can tell us if a higher risk score is correlated with a higher chance of re-arrest, we argue that it is problematic to make broad claims about whether a tool is racially biased solely based on AUC values.

This metric also ignores the existence of the thresholds that create groupings like “high risk” and “low risk.” These groupings are crucial, and they are not neutral. When the DOJ used PATTERN to inform release decisions at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, they reportedly secretly altered the threshold that determines whether someone is classified as “minimum risk,” meaning far fewer people would qualify to be considered for release.

We argue that any choice about who gets classified into each of these groups represents an implicit policy judgement about the value of freedom and harms of incarceration. Though this change may have been framed as a decision based on data and mathematics, the DOJ essentially made a policy choice about the societal costs of releasing people to their homes and families relative to the costs of incarceration, arguably manipulating thresholds to effect policy decisions.

So, why should civil rights advocates care about this?

In our work assessing the impacts of automated systems, we see this dynamic repeatedly: government agencies rely on sloppy use of scientific concepts, such as using AUC as a seal of approval to justify the use of a model. Agencies or tool developers then set thresholds that determine whether people are kept in prison during a pandemic, whether they are jailed prior to trial, or whether their homes are entered without warrants.

Yet this threshold-setting and manipulation often happens behind closed doors. Mathematical rigor is often prioritized over the input of civil rights advocates and impacted communities, and civil rights advocates and impacted communities are routinely excluded from crucial conversations about how these tools are designed or whether they should be designed at all. Ultimately, this veiling of policy with mathematics has grave consequences for our ability to demand accountability from those who seek to deploy risk assessments.

How can we ensure that government agencies and other decision-makers are held accountable for the potential harm that risk assessment tools may cause?

We must insist that tool designers and governments lift the veil on the critical policy decisions embedded in these tools — from the data sets used to develop these tools, to what risks the tools assess, to how the tools ultimately box people into risk categories. This is especially true for criminal and civil defense attorneys whose clients face life-altering consequences from being labeled “too risky.” Data scientists and other experts must help communities cut through the technical language of tool designers to lay bare their policy implications. Better yet, advocates and impacted communities must insist on a seat at the table to make threshold and other decisions that represent implicit or explicit policymaking in the creation of risk assessments.

To push for this change, we’ve created a resource for advocates, lawyers, and impacted communities, including questions you should feel empowered to ask when government agencies or developers make claims about risk assessment tools:

Published August 8, 2023 at 04:38PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/4HtrkMN