Saturday, 30 September 2023

Sri Lanka: Technical Assistance Report-Governance Diagnostic Assessment

Published September 30, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Friday, 29 September 2023

Republic of Armenia: Technical Assistance Report-Residential Property Price Index Statistics Mission

Published September 29, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Vietnam: Technical Assistance Report-Macroeconomic Framework Technical Assistance–Ministry of Planning and Investment: Scoping Mission

Published September 29, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Thursday, 28 September 2023

ACLU: As a New Term Begins, Where Does the Supreme Court Stand on Criminal Justice?

It’s that time of year again: The U.S. Supreme Court will convene next week for a new term. While the last few terms have seen the court deliver seismic decisions on abortion, affirmative action, and voting rights, they’ve been tougher to read in another crucial area: criminal justice.

So, before the term begins on October 2, let’s try to break this down. Here’s a look at where the court stands on criminal law reform issues today, and two cases to keep an eye on.

Not rocking the boat in wide-reaching cases

In general, the Supreme Court’s recent criminal law decisions have been less polarized compared to other areas like abortion and affirmative action. Though the court often rules in favor of the government in criminal matters, it sides with defendants in a surprising number of cases.

There’s just one catch: The court tends to side with defendants under narrow circumstances, when their decisions won’t have a wide-ranging impact.

Take the 2020 case of Ramos v. Louisiana, which invalidated non-unanimous juries. The ruling required juries to reach unanimous guilty verdicts in trials for serious felony crimes. In so doing, the 6-3 majority acknowledged the roots of non-unanimous juries in the enforcement of Jim Crow. Blurring ideological lines, conservative justice Neil Gorsuch penned the majority opinion, joined by fellow conservatives Brett Kavanaugh and Clarence Thomas, while liberal justice Elena Kagan joined an opinion written by conservative justice Samuel Alito, along with conservative Chief Justice John Roberts. This decision could help prevent innocent defendants from being convicted and safeguard against decisions based on racial bias.

However, this ruling only affected Louisiana and Oregon, the last two states to maintain this practice. Further, due to excessively harsh sentencing laws and coercive plea bargaining tactics, jury trials have become a rarity. And the court ruled the very next term that its decision is not retroactive, so it can’t be applied to past felony cases; the states will be left to decide which older cases it applies to. The court went even further and held it would no longer apply new rules of criminal procedure retroactively at all.

Taking a tough stance on federal habeas law

The one consistent throughline in the court’s rulings involving the criminal legal system is its continued draconian interpretation of federal habeas law. For instance, in Jones v. Hendrix, the Supreme Court ruled that federally incarcerated people who are actually innocent — because the Supreme Court later found the conduct was not criminal — can still be held in prison without any ability to petition a court for release.

Basically, the Supreme Court used a strict interpretation of the federal Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA). The law states that incarcerated people generally can’t challenge their conviction more than once. There are two exceptions: when new evidence demonstrating innocence emerges, or when a new rule of constitutional law is made retroactive by the Supreme Court. According to the court, Jones’ situation did not fit either exception. He fell into a gaping hole in federal habeas: Though he was actually innocent, it was because of a new legal ruling, not new evidence, and that ruling was based on a federal statute, rather than the Constitution. There were other ways to interpret the statute, but the court rejected them. So an innocent man sits in jail to this day, with no judicial recourse.

Avoiding the big questions

More broadly, the court has avoided answering important criminal procedural questions. For one, the court recently denied review of the ACLU’s case Hester v. Gentry. That lawsuit challenges the widespread practice in Alabama of detaining people prior to trial for weeks or months simply because they cannot afford cash bail. The case argues this practice is unconstitutional, in part because the right to pretrial liberty is fundamental, and cannot be denied unless the government has a compelling reason. The court has not ruled on these issues in nearly 40 years. In its silence, practices like those in Alabama have proliferated across the country.

The court has also generally declined to review cases challenging the qualified immunity doctrine, such as Novak v. Parma. Qualified immunity prevents government officials and law enforcement officers from being sued for money damages for violating someone’s rights. The ACLU has long called for the court or Congress to abolish this doctrine. After Ohio resident Anthony Novak was arrested for publishing a parody of the Parma Police Department’s Facebook page, he filed a civil lawsuit against the department for violating his First Amendment rights. By rejecting Novak’s appeal, the Supreme Court denied any remedy for this constitutional violation.

As the next term approaches, we’re unlikely to see any major changes in the Supreme Court’s stance on criminal justice issues. One case of interest is Pulsifier v. United States, in which the court will decide whether “and” means “and” or “or” under the 2018 First Step Act in determining whether a defendant qualifies for the “safety valve” provision under federal sentencing law. The safety valve allows federal judges to sentence defendants convicted of certain drug crimes below the mandatory minimum, an effort by Congress to mitigate some of the harms from the failed war on drugs. Though a favorable result maintaining broad access to the safety valve is uncertain, it is likely made more plausible by the fact that relief in the case would be narrow: Judges would not be required to sentence below the mandatory minimum; they would simply have the discretion to do so.

McElrath v. Georgia will likely follow a similar pattern. That case involves a law unique to Georgia that creates an exception to the Double Jeopardy clause, namely, by allowing a defendant to be prosecuted a second time for a crime of which they were previously acquitted. The question rests on whether the jury’s acquittal in the first prosecution was “repugnant,” meaning it was inconsistent with the same jury’s findings of guilt on related charges. The case invites the court to reaffirm the importance of both the Double Jeopardy clause and the right to a jury in criminal cases, which the court may well accept given a victory for the defendant would only directly impact a handful of individuals in a single state.

Wins in either of these cases, while welcome, will not change the fact that the court has staked out a conservative middle ground where it will only advance individual rights in cases with less of a ripple effect, while maintaining an inscrutable combination lock on the courthouse doors for defendants asserting these rights. We’ll be watching closely to see if this trend continues in the new term.

Published September 28, 2023 at 08:49PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/ORMiVwX

ACLU: As a New Term Begins, Where Does the Supreme Court Stand on Criminal Justice?

It’s that time of year again: The U.S. Supreme Court will convene next week for a new term. While the last few terms have seen the court deliver seismic decisions on abortion, affirmative action, and voting rights, they’ve been tougher to read in another crucial area: criminal justice.

So, before the term begins on October 2, let’s try to break this down. Here’s a look at where the court stands on criminal law reform issues today, and two cases to keep an eye on.

Not rocking the boat in wide-reaching cases

In general, the Supreme Court’s recent criminal law decisions have been less polarized compared to other areas like abortion and affirmative action. Though the court often rules in favor of the government in criminal matters, it sides with defendants in a surprising number of cases.

There’s just one catch: The court tends to side with defendants under narrow circumstances, when their decisions won’t have a wide-ranging impact.

Take the 2020 case of Ramos v. Louisiana, which invalidated non-unanimous juries. The ruling required juries to reach unanimous guilty verdicts in trials for serious felony crimes. In so doing, the 6-3 majority acknowledged the roots of non-unanimous juries in the enforcement of Jim Crow. Blurring ideological lines, conservative justice Neil Gorsuch penned the majority opinion, joined by fellow conservatives Brett Kavanaugh and Clarence Thomas, while liberal justice Elena Kagan joined an opinion written by conservative justice Samuel Alito, along with conservative Chief Justice John Roberts. This decision could help prevent innocent defendants from being convicted and safeguard against decisions based on racial bias.

However, this ruling only affected Louisiana and Oregon, the last two states to maintain this practice. Further, due to excessively harsh sentencing laws and coercive plea bargaining tactics, jury trials have become a rarity. And the court ruled the very next term that its decision is not retroactive, so it can’t be applied to past felony cases; the states will be left to decide which older cases it applies to. The court went even further and held it would no longer apply new rules of criminal procedure retroactively at all.

Taking a tough stance on federal habeas law

The one consistent throughline in the court’s rulings involving the criminal legal system is its continued draconian interpretation of federal habeas law. For instance, in Jones v. Hendrix, the Supreme Court ruled that federally incarcerated people who are actually innocent — because the Supreme Court later found the conduct was not criminal — can still be held in prison without any ability to petition a court for release.

Basically, the Supreme Court used a strict interpretation of the federal Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA). The law states that incarcerated people generally can’t challenge their conviction more than once. There are two exceptions: when new evidence demonstrating innocence emerges, or when a new rule of constitutional law is made retroactive by the Supreme Court. According to the court, Jones’ situation did not fit either exception. He fell into a gaping hole in federal habeas: Though he was actually innocent, it was because of a new legal ruling, not new evidence, and that ruling was based on a federal statute, rather than the Constitution. There were other ways to interpret the statute, but the court rejected them. So an innocent man sits in jail to this day, with no judicial recourse.

Avoiding the big questions

More broadly, the court has avoided answering important criminal procedural questions. For one, the court recently denied review of the ACLU’s case Hester v. Gentry. That lawsuit challenges the widespread practice in Alabama of detaining people prior to trial for weeks or months simply because they cannot afford cash bail. The case argues this practice is unconstitutional, in part because the right to pretrial liberty is fundamental, and cannot be denied unless the government has a compelling reason. The court has not ruled on these issues in nearly 40 years. In its silence, practices like those in Alabama have proliferated across the country.

The court has also generally declined to review cases challenging the qualified immunity doctrine, such as Novak v. Parma. Qualified immunity prevents government officials and law enforcement officers from being sued for money damages for violating someone’s rights. The ACLU has long called for the court or Congress to abolish this doctrine. After Ohio resident Anthony Novak was arrested for publishing a parody of the Parma Police Department’s Facebook page, he filed a civil lawsuit against the department for violating his First Amendment rights. By rejecting Novak’s appeal, the Supreme Court denied any remedy for this constitutional violation.

As the next term approaches, we’re unlikely to see any major changes in the Supreme Court’s stance on criminal justice issues. One case of interest is Pulsifier v. United States, in which the court will decide whether “and” means “and” or “or” under the 2018 First Step Act in determining whether a defendant qualifies for the “safety valve” provision under federal sentencing law. The safety valve allows federal judges to sentence defendants convicted of certain drug crimes below the mandatory minimum, an effort by Congress to mitigate some of the harms from the failed war on drugs. Though a favorable result maintaining broad access to the safety valve is uncertain, it is likely made more plausible by the fact that relief in the case would be narrow: Judges would not be required to sentence below the mandatory minimum; they would simply have the discretion to do so.

McElrath v. Georgia will likely follow a similar pattern. That case involves a law unique to Georgia that creates an exception to the Double Jeopardy clause, namely, by allowing a defendant to be prosecuted a second time for a crime of which they were previously acquitted. The question rests on whether the jury’s acquittal in the first prosecution was “repugnant,” meaning it was inconsistent with the same jury’s findings of guilt on related charges. The case invites the court to reaffirm the importance of both the Double Jeopardy clause and the right to a jury in criminal cases, which the court may well accept given a victory for the defendant would only directly impact a handful of individuals in a single state.

Wins in either of these cases, while welcome, will not change the fact that the court has staked out a conservative middle ground where it will only advance individual rights in cases with less of a ripple effect, while maintaining an inscrutable combination lock on the courthouse doors for defendants asserting these rights. We’ll be watching closely to see if this trend continues in the new term.

Published September 28, 2023 at 04:19PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/VEmpPzv

Wednesday, 27 September 2023

Vietnam: 2023 IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Vietnam

Published September 27, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

ACLU: 10 Advocates on Why They Won’t Stand for Classroom Censorship

Right now, educators across the country are welcoming a new class of learners. At the same time laws that censor teachers and stifle classroom conversations about race, gender, and sexuality are threatening our right to an inclusive education.

Under the guise of “transparency” and “parents’ rights,”’ state lawmakers have been pushing bills that regulate how educators address systemic racism, LGBTQ+ issues, and other so-called “divisive concepts.” The ability to discuss and debate ideas, even those that some may find uncomfortable, is a crucial part of our democracy and barring discussion of our history or lived experiences is anathema to free speech.

The ACLU has challenged classroom censorship laws in Florida, New Hampshire and Oklahoma to protect educators’ and students’ right to teach and learn. This back-to-school season, we stand with the teachers, students, parents, and school systems on the frontline of our fight against classroom censorship.

We asked our audience to share how diverse teaching has impacted their lives and why they, too, support access to an inclusive education system.

“Finding the color purple on the shelf of my high school library changed my life.” – Naomi Olivia, advocate for the right to learn

“If you don’t teach diversity and the truth as it was, we risk repeating the horrors of the past. Not only that, but we actively harm and further oppress the voices of the marginalized.” – Dezz, advocate for the right to learn

“History isn’t always pretty. Knowing what really happened [is] critical to understanding our past and how [it is] impacting our present.” – Jeff W., advocate for the right to learn

“People should be able to learn whatever they wish to learn.” – Daniel L., advocate for the right to learn

“How are we supposed to help bring about a better world for all when we are no longer supposed to learn about and talk about other people and their life experiences. “ – Kathy G., advocate for the right to learn

“Let’s stop being paranoid about children learning diversity, it won’t harm them, in fact it will bring good to the world as not only will it help them with their own self discovery, it will help them be more kind, caring, empathetic, and understanding towards those who are different from them.” – Kortniey J., advocate for the right to learn

“I am a parent, a grandparent, and a recently retired public school teacher and school librarian. My school library was a safe place for all of the students who felt different, left out, or who felt they could not talk to their parents.” – Ann, advocate for the right to learn

“I grew up in the 1970s in a pretty progressive city. We were starting to talk about race then. What I didn’t learn in school left me ignorant about the world around me and my role in it.” – Anonymous advocate for the right to learn

“As a parent raising a non-binary child in the early 2000s, I again didn’t know what I didn’t know, didn’t recognize what I was seeing. With no representation or discussion of gender identity in schools at that time, they truly were alone and struggling.” – Anonymous advocate for the right to learn

“By not teaching our kids about themselves and about others, by depriving them of the images and stories and histories of diverse people and cultures, we deprive them and ultimately our society of the opportunity to reach our full potential.” – Anonymous advocate for the right to learn

Published September 27, 2023 at 09:37PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/wWhC6Mo

ACLU: 10 Advocates on Why They Won’t Stand for Classroom Censorship

Right now, educators across the country are welcoming a new class of learners. At the same time laws that censor teachers and stifle classroom conversations about race, gender, and sexuality are threatening our right to an inclusive education.

Under the guise of “transparency” and “parents’ rights,”’ state lawmakers have been pushing bills that regulate how educators address systemic racism, LGBTQ+ issues, and other so-called “divisive concepts.” The ability to discuss and debate ideas, even those that some may find uncomfortable, is a crucial part of our democracy and barring discussion of our history or lived experiences is anathema to free speech.

The ACLU has challenged classroom censorship laws in Florida, New Hampshire and Oklahoma to protect educators’ and students’ right to teach and learn. This back-to-school season, we stand with the teachers, students, parents, and school systems on the frontline of our fight against classroom censorship.

We asked our audience to share how diverse teaching has impacted their lives and why they, too, support access to an inclusive education system.

“Finding the color purple on the shelf of my high school library changed my life.” – Naomi Olivia, advocate for the right to learn

“If you don’t teach diversity and the truth as it was, we risk repeating the horrors of the past. Not only that, but we actively harm and further oppress the voices of the marginalized.” – Dezz, advocate for the right to learn

“History isn’t always pretty. Knowing what really happened [is] critical to understanding our past and how [it is] impacting our present.” – Jeff W., advocate for the right to learn

“People should be able to learn whatever they wish to learn.” – Daniel L., advocate for the right to learn

“How are we supposed to help bring about a better world for all when we are no longer supposed to learn about and talk about other people and their life experiences. “ – Kathy G., advocate for the right to learn

“Let’s stop being paranoid about children learning diversity, it won’t harm them, in fact it will bring good to the world as not only will it help them with their own self discovery, it will help them be more kind, caring, empathetic, and understanding towards those who are different from them.” – Kortniey J., advocate for the right to learn

“I am a parent, a grandparent, and a recently retired public school teacher and school librarian. My school library was a safe place for all of the students who felt different, left out, or who felt they could not talk to their parents.” – Ann, advocate for the right to learn

“I grew up in the 1970s in a pretty progressive city. We were starting to talk about race then. What I didn’t learn in school left me ignorant about the world around me and my role in it.” – Anonymous advocate for the right to learn

“As a parent raising a non-binary child in the early 2000s, I again didn’t know what I didn’t know, didn’t recognize what I was seeing. With no representation or discussion of gender identity in schools at that time, they truly were alone and struggling.” – Anonymous advocate for the right to learn

“By not teaching our kids about themselves and about others, by depriving them of the images and stories and histories of diverse people and cultures, we deprive them and ultimately our society of the opportunity to reach our full potential.” – Anonymous advocate for the right to learn

Published September 27, 2023 at 05:07PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/OxCIYPL

Tuesday, 26 September 2023

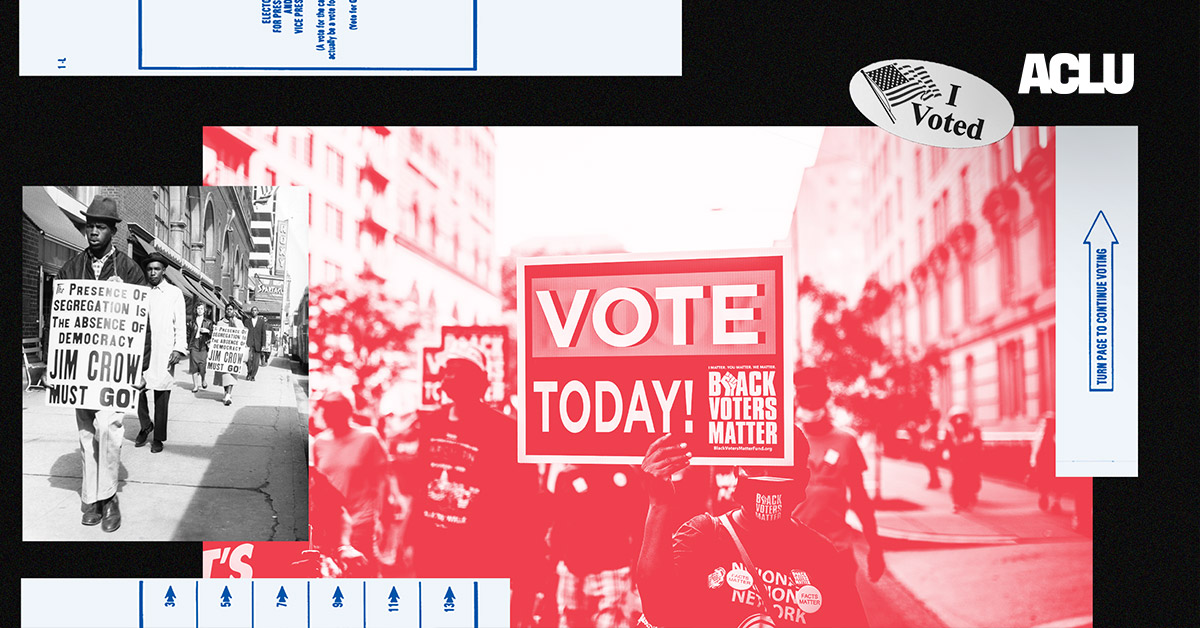

ACLU: Florida’s Statewide Prosecution of Voting with a Past Conviction is Unlawful

After Ronald Miller registered to vote in 2020, the State of Florida sent him a voter information card in the mail. Mr. Miller did not find out that a prior felony conviction made him ineligible to register or vote until, in 2022, Florida state officers arrested him. Now, Mr. Miller is one of several returning citizens that Florida’s Office of Statewide Prosecution (OSP) is prosecuting for making what appear to be good-faith mistakes about their voter eligibility. Rather than helping their citizens understand Florida’s complicated voter eligibility rules, the State has instead resorted to these intimidating, anti-democratic prosecutions.

Today, we — along with our partners at the ACLU of Florida, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and the Brennan Center for Justice — filed an amicus brief in Mr. Miller’s case highlighting OSP’s unlawful prosecution against Mr. Miller and other returning citizens in Florida, which disproportionately implicate Black citizens.

Florida’s System for Voting Rights Restoration: An “Administrative Train Wreck”

In 2018, Florida voters passed Amendment 4, which aimed to permanently end felony disenfranchisement in the state and restored voting rights for returning citizens who had completed the terms of their sentences. That amendment would’ve restored the right to vote for an estimated 1.4 million people. But, the following year, Florida’s legislature passed a new law requiring returning citizens pay off certain fines and fees before they can regain their right to vote. The ACLU and our partners challenged Florida’s pay-to-vote system for returning citizens, but were ultimately unsuccessful.

Now, in the words of one federal court, Florida’s system of rights restoration for returning citizens is an “administrative train wreck.” Florida has essentially abdicated its responsibility to returning citizens in the state, refusing to provide meaningful guidance to individuals looking to navigate this byzantine system and figure out if they are eligible or not. When a registrant is ineligible, that should be flagged by the state before the person mistakenly casts a ballot, but Florida hasn’t consistently provided registrants with that clarity. In many cases, Florida has misled its citizens about their voter eligibility, including by sending them voter information cards in the mail.

And after telling multiple federal courts that returning citizens who made good-faith mistakes about their voter eligibility need not fear prosecution, the State has instead decided to prosecute nearly two dozen individuals for what appear to be honest mistakes. Fifteen out of the 19 returning citizens being prosecuted by OSP are Black.

Florida’s Statewide Prosecution: An Unbounded Expansion of Authority

Because Florida’s system for knowing whether you’re eligible to vote is so confusing, some of Florida’s local state attorneys have declined to prosecute people who try to register or vote while mistakenly thinking they’re eligible to do so. And for good reason: Voting while ineligible is a crime in Florida, but only when someone knows they’re ineligible and purposefully decides to vote anyway. People like Mr. Miller who don’t know and are never told they’re ineligible, and try to vote, aren’t guilty of a crime. That’s why, for example, one local prosecutor last year decided not to prosecute some people in a similar situation.

But just before a major election in 2022, Gov. Ron DeSantis announced OSP’s arrests of 19 returning citizens — including Mr. Miller — for allegedly voting while ineligible in 2020. He called those arrests the “opening salvo” of his state government’s efforts to prosecute voting where local prosecutors hadn’t. OSP, however, only has authority to prosecute crimes that happen in multiple judicial circuits. Registering to vote or voting while ineligible, of course, happens only in one location. So, several state courts have dismissed the charges against Mr. Miller and some other returning citizens, finding that OSP didn’t have authority to bring the prosecutions. The State has appealed the dismissal.

Our amicus brief, filed before Florida’s intermediate appellate court, argues that the OSP doesn’t have the power to prosecute Mr. Miller. That’s because it was created to go after organized, complex, criminal conspiracies that are hard for one local prosecutor’s office to handle alone. The legislators who authorized OSP didn’t intend for it to wield its power to prosecute people like Mr. Miller, who vote or register because of a good-faith mistake. Instead, they were careful to give it a limited authority over only some kinds of crimes and not to usurp the discretion of local prosecutors. The State’s argument — that registering and voting occurs throughout the state as a whole, so any voting offense is a statewide crime — blows up that balance entirely. Under that theory, the OSP would have prosecutorial power over almost any offense. The State, in other words, wants OSP to have boundless authority.

Confusion and Fear Among Black Voters

Florida’s attempt to assert free reign to carry out unjust voter prosecutions, instead of fixing its registration system, is just one of many ways it has tried to chill and suppress the votes of Black people in the state. In Florida, one in eight Black people are disenfranchised, twice the rate of non-Black people. Nationwide, Black people are more likely to face jail time for voting violations. Knowing that any simple mistake on a voting form could lead to a prosecution has already made many eligible voters afraid to vote.

These arrests and prosecutions, in other words, are another dramatic attempt at suppressing votes in Florida, particularly for Black citizens. The ACLU and our partners are committed to combatting these shameful prosecutions that work to endanger our democracy.

Published September 26, 2023 at 08:01PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/Fhi3Zfu

ACLU: Florida’s Statewide Prosecution of Voting with a Past Conviction is Unlawful

After Ronald Miller registered to vote in 2020, the State of Florida sent him a voter information card in the mail. Mr. Miller did not find out that a prior felony conviction made him ineligible to register or vote until, in 2022, Florida state officers arrested him. Now, Mr. Miller is one of several returning citizens that Florida’s Office of Statewide Prosecution (OSP) is prosecuting for making what appear to be good-faith mistakes about their voter eligibility. Rather than helping their citizens understand Florida’s complicated voter eligibility rules, the State has instead resorted to these intimidating, anti-democratic prosecutions.

Today, we — along with our partners at the ACLU of Florida, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and the Brennan Center for Justice — filed an amicus brief in Mr. Miller’s case highlighting OSP’s unlawful prosecution against Mr. Miller and other returning citizens in Florida, which disproportionately implicate Black citizens.

Florida’s System for Voting Rights Restoration: An “Administrative Train Wreck”

In 2018, Florida voters passed Amendment 4, which aimed to permanently end felony disenfranchisement in the state and restored voting rights for returning citizens who had completed the terms of their sentences. That amendment would’ve restored the right to vote for an estimated 1.4 million people. But, the following year, Florida’s legislature passed a new law requiring returning citizens pay off certain fines and fees before they can regain their right to vote. The ACLU and our partners challenged Florida’s pay-to-vote system for returning citizens, but were ultimately unsuccessful.

Now, in the words of one federal court, Florida’s system of rights restoration for returning citizens is an “administrative train wreck.” Florida has essentially abdicated its responsibility to returning citizens in the state, refusing to provide meaningful guidance to individuals looking to navigate this byzantine system and figure out if they are eligible or not. When a registrant is ineligible, that should be flagged by the state before the person mistakenly casts a ballot, but Florida hasn’t consistently provided registrants with that clarity. In many cases, Florida has misled its citizens about their voter eligibility, including by sending them voter information cards in the mail.

And after telling multiple federal courts that returning citizens who made good-faith mistakes about their voter eligibility need not fear prosecution, the State has instead decided to prosecute nearly two dozen individuals for what appear to be honest mistakes. Fifteen out of the 19 returning citizens being prosecuted by OSP are Black.

Florida’s Statewide Prosecution: An Unbounded Expansion of Authority

Because Florida’s system for knowing whether you’re eligible to vote is so confusing, some of Florida’s local state attorneys have declined to prosecute people who try to register or vote while mistakenly thinking they’re eligible to do so. And for good reason: Voting while ineligible is a crime in Florida, but only when someone knows they’re ineligible and purposefully decides to vote anyway. People like Mr. Miller who don’t know and are never told they’re ineligible, and try to vote, aren’t guilty of a crime. That’s why, for example, one local prosecutor last year decided not to prosecute some people in a similar situation.

But just before a major election in 2022, Gov. Ron DeSantis announced OSP’s arrests of 19 returning citizens — including Mr. Miller — for allegedly voting while ineligible in 2020. He called those arrests the “opening salvo” of his state government’s efforts to prosecute voting where local prosecutors hadn’t. OSP, however, only has authority to prosecute crimes that happen in multiple judicial circuits. Registering to vote or voting while ineligible, of course, happens only in one location. So, several state courts have dismissed the charges against Mr. Miller and some other returning citizens, finding that OSP didn’t have authority to bring the prosecutions. The State has appealed the dismissal.

Our amicus brief, filed before Florida’s intermediate appellate court, argues that the OSP doesn’t have the power to prosecute Mr. Miller. That’s because it was created to go after organized, complex, criminal conspiracies that are hard for one local prosecutor’s office to handle alone. The legislators who authorized OSP didn’t intend for it to wield its power to prosecute people like Mr. Miller, who vote or register because of a good-faith mistake. Instead, they were careful to give it a limited authority over only some kinds of crimes and not to usurp the discretion of local prosecutors. The State’s argument — that registering and voting occurs throughout the state as a whole, so any voting offense is a statewide crime — blows up that balance entirely. Under that theory, the OSP would have prosecutorial power over almost any offense. The State, in other words, wants OSP to have boundless authority.

Confusion and Fear Among Black Voters

Florida’s attempt to assert free reign to carry out unjust voter prosecutions, instead of fixing its registration system, is just one of many ways it has tried to chill and suppress the votes of Black people in the state. In Florida, one in eight Black people are disenfranchised, twice the rate of non-Black people. Nationwide, Black people are more likely to face jail time for voting violations. Knowing that any simple mistake on a voting form could lead to a prosecution has already made many eligible voters afraid to vote.

These arrests and prosecutions, in other words, are another dramatic attempt at suppressing votes in Florida, particularly for Black citizens. The ACLU and our partners are committed to combatting these shameful prosecutions that work to endanger our democracy.

Published September 26, 2023 at 03:31PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/r69iV71

Friday, 22 September 2023

Botswana: Financial System Stability Assessment

Published September 21, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Honduras: 2023 Article IV Consultation and Requests for an Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility and an Arrangement Under the Extended Credit Facility-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Honduras

Published September 22, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Thursday, 21 September 2023

Angola: First Post-Financing Assessment Discussions-Press Release

Published September 18, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

ACLU: RICO and Domestic Terrorism Charges Against Cop City Activists Send a Chilling Message

The 2020 police killing of George Floyd launched the largest protests in U.S. history and a nationwide reckoning with systemic racism and police brutality. Now, Georgia’s Attorney General Chris Carr has shamefully invoked Floyd’s killing and the subsequent uprising in a sweeping criminal indictment of activists protesting a $90 million Atlanta police training center known as “Cop City.” Carr’s actions must be understood as extreme intimidation tactics that we need to resist. They must not set a precedent.

Last week, Carr obtained indictments against 61 people, alleging violations of the state’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) law, over ongoing efforts to halt construction of Cop City. Indicted activists, including a protest observer, face steep penalties of up to 20 years in prison. Three bail fund organizers face additional money laundering charges, and five people also face state domestic terrorism charges.

The indictment’s theory is shocking, and its combination of charges is unprecedented.

Georgia’s legislature intended RICO to combat organized crime, not to punish protest, civil disobedience, or isolated crimes. Yet according to Carr, opposing construction of Cop City amounts to a criminal conspiracy under the state RICO statute. To make its case, the indictment relies on people’s beliefs and community organizing as the connective tissue for sweeping criminal liability. It devotes 25 pages to vilifying Defend the Atlanta Forest (DTAF), the grassroots movement opposing Cop City’s construction, identifying its “beginnings” in the nationwide protests against George Floyd’s murder and protests in Georgia against the police killing of Atlanta resident Rayshard Brooks, and calling out the movement’s “anarchist ideals.” It paints the provision of mutual aid, the advocacy of collectivism, and even the publishing of zines as hallmarks of a criminal enterprise. In doing so, it flies in the face of First Amendment protections for speech, assembly, and association.

Georgia attorney general Chris Carr speaks at a press conference as Georgia Governor Brian Kemp (on the right) looks on.

Nathan Posner/Shutterstock

While Carr wants to prosecute a protest movement as if it were a full-fledged organized crime ring, much of the alleged conduct is far less severe. For example, the indictment’s list of alleged criminal conduct repeatedly includes: people trying to occupy the forest in which Cop City would be built, reimbursements for protest supplies, and characterization of individuals attempting to join a “mob” to overwhelm the police. Even innocuous acts like buying food, writing “ACAB,” or distributing flyers are made out to be the cornerstones of a nefarious criminal scheme.

To the extent that unlawful conduct such as property crimes could be alleged, Georgia prosecutors could have chosen to press those specific lesser charges. Instead, the indictment haphazardly sweeps many forms of opposition to Cop City, including speech, peaceful protest activities, and minor acts of civil disobedience, into felony violations of Georgia’s anti-racketeering law.

Indeed, Georgia officials have repeatedly chosen to escalate charges beyond any legitimate need. In March of this year, Georgia police stigmatized 42 Cop City activists with arrests for “domestic terrorism.” This is exactly the kind of overreach rights groups warned about and objected to when Georgia’s legislature amended the domestic terrorism law in 2017 to add a harsher punishment — up to 35 years — to property crimes that were already illegal, simply because of accompanying political expression critical of government policy. It’s chilling to see “domestic terrorism” charges formally levied against five people in last week’s indictment.

Taken together, these disproportionate charges send a clear message: Think twice before voicing your dissent. Unfortunately, punitive intimidation tactics against civil rights, social justice, and environmental activists is not new. We do not forget that civil rights movement leaders like Rep. John Lewis and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. were labeled security threats and investigated, monitored, and often arrested — including in Georgia — based on their organizing and civil disobedience in the pursuit of equality. If Georgia’s RICO and “domestic terrorism” laws had been available to prosecutors in the civil rights era, they could easily have been misused to persecute activists.

Today, there is legitimate concern that Georgia’s sweeping indictment could form a playbook for other prosecutors and state officials seeking to stifle political dissent. Several states now have RICO and domestic terrorism laws on the books. But Attorney General Carr’s actions must not set a precedent.

Instead, Georgia should honor a better precedent. Atlanta a critical hub of the modern civil rights movement — and the protection of protest is integral to both our rights and our democracy. Attorney General Carr’s trumped-up and excessive charges against Cop City activists should be dropped immediately.

Published September 21, 2023 at 11:50PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/ClmnJV0

ACLU: RICO and Domestic Terrorism Charges Against Cop City Activists Send a Chilling Message

The 2020 police killing of George Floyd launched the largest protests in U.S. history and a nationwide reckoning with systemic racism and police brutality. Now, Georgia’s Attorney General Chris Carr has shamefully invoked Floyd’s killing and the subsequent uprising in a sweeping criminal indictment of activists protesting a $90 million Atlanta police training center known as “Cop City.” Carr’s actions must be understood as extreme intimidation tactics that we need to resist. They must not set a precedent.

Last week, Carr obtained indictments against 61 people, alleging violations of the state’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) law, over ongoing efforts to halt construction of Cop City. Indicted activists, including a protest observer, face steep penalties of up to 20 years in prison. Three bail fund organizers face additional money laundering charges, and five people also face state domestic terrorism charges.

The indictment’s theory is shocking, and its combination of charges is unprecedented.

Georgia’s legislature intended RICO to combat organized crime, not to punish protest, civil disobedience, or isolated crimes. Yet according to Carr, opposing construction of Cop City amounts to a criminal conspiracy under the state RICO statute. To make its case, the indictment relies on people’s beliefs and community organizing as the connective tissue for sweeping criminal liability. It devotes 25 pages to vilifying Defend the Atlanta Forest (DTAF), the grassroots movement opposing Cop City’s construction, identifying its “beginnings” in the nationwide protests against George Floyd’s murder and protests in Georgia against the police killing of Atlanta resident Rayshard Brooks, and calling out the movement’s “anarchist ideals.” It paints the provision of mutual aid, the advocacy of collectivism, and even the publishing of zines as hallmarks of a criminal enterprise. In doing so, it flies in the face of First Amendment protections for speech, assembly, and association.

Georgia attorney general Chris Carr speaks at a press conference as Georgia Governor Brian Kemp (on the right) looks on.

Nathan Posner/Shutterstock

While Carr wants to prosecute a protest movement as if it were a full-fledged organized crime ring, much of the alleged conduct is far less severe. For example, the indictment’s list of alleged criminal conduct repeatedly includes: people trying to occupy the forest in which Cop City would be built, reimbursements for protest supplies, and characterization of individuals attempting to join a “mob” to overwhelm the police. Even innocuous acts like buying food, writing “ACAB,” or distributing flyers are made out to be the cornerstones of a nefarious criminal scheme.

To the extent that unlawful conduct such as property crimes could be alleged, Georgia prosecutors could have chosen to press those specific lesser charges. Instead, the indictment haphazardly sweeps many forms of opposition to Cop City, including speech, peaceful protest activities, and minor acts of civil disobedience, into felony violations of Georgia’s anti-racketeering law.

Indeed, Georgia officials have repeatedly chosen to escalate charges beyond any legitimate need. In March of this year, Georgia police stigmatized 42 Cop City activists with arrests for “domestic terrorism.” This is exactly the kind of overreach rights groups warned about and objected to when Georgia’s legislature amended the domestic terrorism law in 2017 to add a harsher punishment — up to 35 years — to property crimes that were already illegal, simply because of accompanying political expression critical of government policy. It’s chilling to see “domestic terrorism” charges formally levied against five people in last week’s indictment.

Taken together, these disproportionate charges send a clear message: Think twice before voicing your dissent. Unfortunately, punitive intimidation tactics against civil rights, social justice, and environmental activists is not new. We do not forget that civil rights movement leaders like Rep. John Lewis and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. were labeled security threats and investigated, monitored, and often arrested — including in Georgia — based on their organizing and civil disobedience in the pursuit of equality. If Georgia’s RICO and “domestic terrorism” laws had been available to prosecutors in the civil rights era, they could easily have been misused to persecute activists.

Today, there is legitimate concern that Georgia’s sweeping indictment could form a playbook for other prosecutors and state officials seeking to stifle political dissent. Several states now have RICO and domestic terrorism laws on the books. But Attorney General Carr’s actions must not set a precedent.

Instead, Georgia should honor a better precedent. Atlanta a critical hub of the modern civil rights movement — and the protection of protest is integral to both our rights and our democracy. Attorney General Carr’s trumped-up and excessive charges against Cop City activists should be dropped immediately.

Published September 21, 2023 at 07:20PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/twkSZgo

Ecuador: Financial System Stability Assessment

Published September 21, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Tuesday, 19 September 2023

Monday, 18 September 2023

Kuwait: 2023 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; and Staff Report

Published September 18, 2023 at 07:00AM

Read more at imf.org

Friday, 15 September 2023

ACLU: On the Frontlines of the Fight Against Classroom Censorship

When Anthony Crawford was in junior high school, he was kicked out of his AP History class one February after he asked the teacher when the class would learn about Black History Month.

“My question made the teacher uncomfortable. I remember his face turning red. He said, ‘You’re not going to disrupt my class, so please step out.’ So I tossed the books on the floor and left the class.”

Crawford never forgot the incident.

Two decades later, he proudly educates ninth graders about the very issues his teachers refused to teach him. At Millwood High School in Oklahoma City, he has crafted a curriculum that examines the systemic ways race and gender impact our lives.

When one walks into his classroom, the first thing they might notice is a colorful poster near the whiteboard with the words “Black History Year” spelled out in block letters. (“Month” had been crossed out and replaced.) Surrounding it are student projects about Nat Turner, Rosa Parks, the Black Panthers, and more.

“Most of the time, my students are the ones who want to talk about race and gender because these are the issues they deal with in their everyday lives,” Crawford told the ACLU last year. “It helps them make sense of what they witness when they step outside school. It also helps them understand themselves, their communities, and each other.”

Illustration by Michael DeForge

In addition to being a passionate educator, Crawford is also a plaintiff in a landmark lawsuit filed by the ACLU, the ACLU of Oklahoma, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under the Law, and pro bono counsel Schulte, Roth & Zabel: Black Emergency Response Team (BERT) v. O’Connor, which challenges a classroom censorship bill passed in Oklahoma, HB 1775.

Signed into law by Gov. Kevin Stitt in May 2021, the legislation restricts teachers and students alike from discussing race or gender in the classroom. Upon approving the bill, Stitt stated that “not one cent of taxpayer money should be used to define and divide young Oklahomans about their race or sex.”

Under the enforcement of this law, educators who violate it can lose their license to teach, and schools can even lose accreditation. The law’s broad language has been interpreted by educators and First Amendment experts as an attempt to deny historical facts, restrict academic freedom, and silence the experiences of marginalized groups. The effort to constrain free speech in the classroom reflects a broader movement by state legislators to restrict civil liberties across the board, including voting rights, LGBTQ equality, and gender equality.

“School officials specifically instructed us to avoid books by authors of color and women authors, leaving two books written by white men — The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald and The Crucible by Arthur Miller — as our only remaining anchor texts,” Regan Killackey told the ACLU last year. An English teacher at Edmond Memorial High School in Edmond, Oklahoma, Killackey is also a plaintiff in Bert v. O’Connor. His previous lesson plan had included works such as To Kill a Mockingbird and Their Eyes Were Watching God.

“[It] is detrimental to all my students. In essence, it prohibits me from doing my job,” said Killackey.

Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a scholarly framework developed by the late Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Charles R. Lawrence III, Mari Matsuda, and others that examine the impact of race on our institutions and is commonly only taught at the graduate school level. It has become the latest obsession of conservative politicians who wish to put an abrupt stop to classroom conversations about race and exploit white voters’ fears in advance of the midterm elections. Though CRT, as such, is not typically taught in K–12 education, it has become a catch-all phrase that includes social-emotional learning, culturally responsive education, and anti-racism.

“Over the last few decades, we’ve had significant progress in making sure that curricula are more reflective of the diversity of students’ experiences and identities, and also present a more honest accounting of our history, the good, the bad, and the ugly,” says Emerson Sykes, senior staff attorney with the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project.

“The education research is clear about the fact that inclusive education improves students’ understanding, improves their behavior, and even improves their academic performance.”

Sykes believes we’re now seeing a backlash to that improvement in school curricula and advancements in our national dialogue about race. The fight over CRT is where many white Americans are “pouring all of the racial anxieties that they have.”

In case you thought the architects of this Oklahoma bill were original in their thinking, parts of HB 1775 were copied verbatim from an executive order from President Donald Trump aimed at censoring government contractors in a similar way. The 2020 executive order was an attack on racial sensitivity training in the federal ranks, referring to these teachings as “divisive, un-American propaganda training sessions.”

Though the executive order was partially blocked on constitutional grounds and it was quickly withdrawn by President Biden, it still signaled to Trump’s base what type of legislation they could introduce at the local and state levels to achieve the desired chilling effect on educators. Trump’s executive order galvanized classroom censorship groups to mimic Trump’s bill with their own.

The summer of 2020 saw unprecedented, worldwide demonstrations for the Black Lives Matter movement after the murder of George Floyd by a Minnesota police officer. It was a centuries overdue moment of racial reckoning against our country’s history, and ugly truths that had been simmering just beneath the veneer of America’s status quo boiled over, spilling out into the streets for weeks on end.

“Racial justice messages were strewn everywhere. Even corporations were getting behind these ideas, and we felt like we were making some significant society-wide progress in our conversation about race. In the wake of that is when President Trump introduced the executive order,” says Sykes. “In many cases, including in Oklahoma, what we’ve seen is a direct copying and pasting from Trump’s executive order. Oftentimes, it’s tweaked. They add a provision or they subtract one to adapt to the local circumstances.”

Bills similar to HB 1775 featuring language that mirrors Trump’s executive order have been cropping up across the country, with 10 states and counting passing them into law. And there are more on the way: In 2022 alone, state legislatures introduced more than 111 new bills across 33 states, many of which explicitly targeted K-12 schools.

This flood of legislation echoes recent state efforts to enact laws that codify voter suppression and criminalize health care for transgender minors. This movement in the classroom may have the impression of a spontaneous grassroots coalition of concerned parents, but that’s not the case. As an investigative report from Education Week revealed, it’s the result of a very strategic and quickly moving assault on historically accurate education by well-resourced, interconnected conservative think tanks. “Impeccably organized” were the words a school district equity officer from the South used to describe the work of groups in their city.

A recent study from the UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access concluded that nearly 18 million students in public school, which is more than one-third of all K–12 students in the nation, have been affected by these classroom censorship efforts. The harm is incalculable.

From the UCLA study, one teacher anonymously shared that they have “avoided subjects I usually would’ve taught because I don’t want to be accused of indoctrinating … White students in my district have become empowered to deny white privilege and say that it is ‘reverse racism,’ [and people] completely dismiss voices from [people of color].”

Another worried teacher said in the survey that the legislation in their state has “taken away the ability to teach actual history and critical thought. They are taking away all nuance and deeper thought, stripping the subject of its actual value.… Students will not be able to effectively investigate the world around them.”

And even more important is the hostile learning environment this can create for students with marginalized identities.

Lilly Amechi, a plaintiff in BERT v. O’Connor, an undergraduate student at the University of Oklahoma, and a member of BERT, says, “To students of color, it sends a message that there is no willingness for people to understand our experiences. The reality is that race pervades the classroom even when it’s not the main subject.”

Sykes, who comes from a long line of teachers and educators, believes this spate of laws hurts students and attempts to take schools backward: “It’s trying to reinforce white supremacy for another generation.”

These bills aren’t going uncontested. The ACLU is mobilizing inside and outside of the courts to protect the First Amendment and academic freedom, as it has for more than a century. In addition to the ongoing Oklahoma lawsuit and a similar case in New Hampshire, in states like Idaho, ACLU affiliates are striving to educate teachers, students, parents, and activists about these forms of legislation and the rights that they possess.

In a violation of free speech, Idaho was one of the first states to introduce and pass an “anti-discrimination” measure that blocks teachers at schools and universities from discussing race or racism in class.

“They want a future where white folks dominate, continue to dominate, and are not made to feel badly about that,” says Aadika Singh, the legal director of the ACLU of Idaho. “Educators all throughout the state are really being pressed with this assumption that they are making white kids feel bad for having honest conversations and teaching the facts about race and gender.”

In Boise, Singh and other lawyers and researchers connected with more than 100 students and educators in the wake of increased classroom censorship and concluded that what the state needed was “education about education,” pivoting away from a typical litigation route. The ACLU of Idaho hosted trainings and workshops for educators and have focused their efforts on reducing the harm of the new law. They created a comprehensive toolkit around what was safe to teach in the classroom and the extent of educators’ academic freedom. An employment attorney was even brought in to advise teachers on what to do if they have to legally challenge a disciplinary action from school administrators.

“There’s this self-censorship where you have teachers saying, ‘I’m just not even a teacher anymore, I’m not going to teach this material because I might lose my job.’ It was very clear that people needed reassurance, needed confidence, and needed to be empowered,” adds Singh.

And at some universities like the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, educators are taking it a step further to expand rather than constrict dialogue. At the USC Gould School of Law, there’s a glimmer of a future where teachers and students are welcomed to think critically about themselves and the society they inhabit.

In 2021, Camille Gear Rich, the Dorothy Nelson Professor of Law and Sociology at the Gould School of Law, was a key advocate for a mandatory course for students that implores them to not only think about the history of bias and discrimination in the United States but also to understand the present-day impact of it within legal contexts. Rich and other faculty advocates were inspired to create the course after a culmination of Trump-era events in 2020, and their goal is to provide students, who may have different levels of exposure to America’s racial struggles, with a “foundational understanding of the facts.”

“Classroom censorship threatens to make the educational project in American schools incoherent. It undermines the ability to tell a logical story about the events of the United States,” she says. In what really feels like a fight for the future, she stresses the importance of learning from our past so that society doesn’t continue to repeat the same mistakes.

“Sometimes people worry that if their child learns about some of the shameful moments in America’s history, they will feel less proud of America or less connected to a patriotic outlook,” says Rich. “But it’s precisely the opposite. America is at its best when it takes into account the needs of all its people. That’s what gives students the motivation to feel a part of the American story and commit to making their own mark on that story.”

Sykes, who is African American, believes that all students have the right to learn an honest accounting of our country’s past and present and that efforts to wipe this out not only violate the First Amendment but run counter to the best interests of future generations.

“As a kid, I learned a whitewashed history,” he says. “The experiences of not seeing yourself reflected in your curriculum resonates deeply with me. The harm of that is something I continue to carry.”

Book Bans Get a New Chapter

Book bans may feel like a relic of a less enlightened past, but this practice has re-emerged with a vengeance. Last year, the American Library Association reported more than 700 challenges to various books in school libraries, with primarily authors of color and LGBTQ authors facing bans.

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, Lawn Boy by Jonathan Evison, Heather Has Two Mommies by Lesléa Newman, and All Boys Aren’t Blue by George Johnson have all been targeted for exclusion in K–12 schools.

Earlier this year, the ACLU filed a lawsuit on behalf of students, parents, and local NAACP chapters challenging the Wentzville R-IV School District’s decision to remove some of the aforementioned books, as well as others discussing race and gender, from its libraries.

Students have a First Amendment right to access information in their school libraries. That includes Black, LGBTQ, and immigrant students having the ability to read books reflecting their own experiences, and the rights of all students to have access to viewpoints different from their own.

Support the right to learn by taking action at aclu.org/righttolearn.

This article originally appeared in the ACLU magazine. Join us today to receive the next issue. The article has been updated to include current data on classroom censorship legislation.

Published September 15, 2023 at 08:09PM

via ACLU https://ift.tt/7cpaOVn